Sort of a local Million Dollar Baby story, here’s a piece about a female boxer who, as the headline says, refused to let age, motherhood or being a woman stand in her way of her dream to go pro.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 11, 2001

Text:

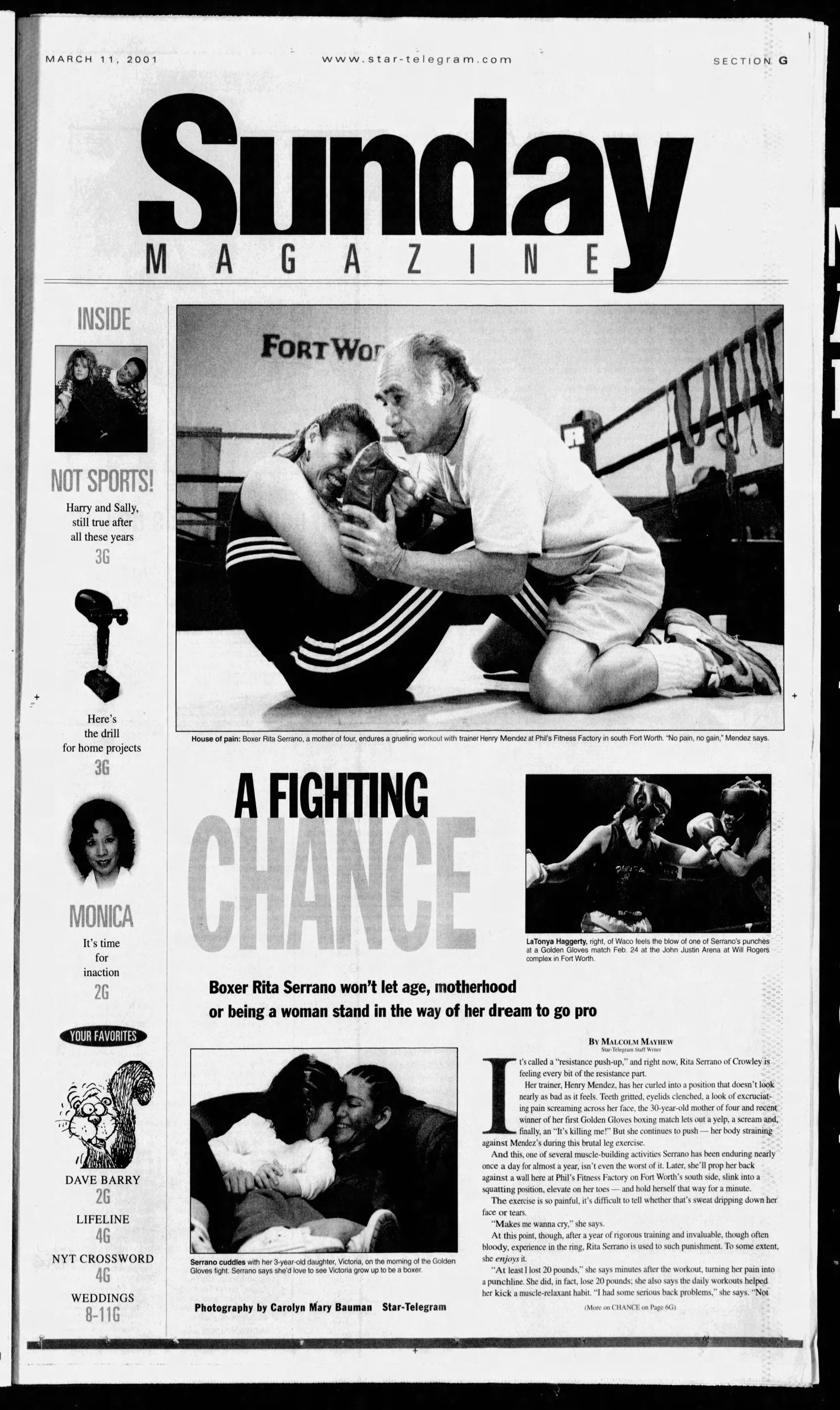

It’s called a “resistance push-up,” and right now, Rita Serrano of Crowley is feeling every bit of the resistance part.

Her trainer, Henry Mendez, has her curled into a position that doesn’t look nearly as bad as it feels. Teeth gritted, eyelids clenched, a look of excruciating pain screaming across her face, the 30-year-old mother of four and recent winner of her first Golden Gloves boxing match lets out a yelp, a scream and, finally, an “It’s killing me!” But she continues to push – her body straining against Mendez’s during this brutal leg exercise.

And this, one of several muscle-building activities Serrano has been enduring nearly once a day for almost a year, isn’t even the worst of it. Later, she’ll prop her back against a wall here at Phil’s Fitness Factory on Fort Worth’s south side, slink into a squatting position, elevate on her toes – and hold herself that way for a minute.

The exercise is so painful, it’s difficult to tell whether that’s sweat dripping down her face or tears.

“Makes me wanna cry,” she says.

At this point, though, after a year of rigorous training and invaluable, though often bloody, experience in the ring, Rita Serrano is used to such punishment. To some extent, she enjoys it.

“At least I lost 20 pounds,” she says minutes after the workout, turning her pain into a punchline. She did, in fact, lose 20 pounds; she also says the daily workouts helped her kick a muscle-relaxant habit. “I had some serious back problems,” she says. “Not anymore. Working out every day helped fix my back more than any painkiller.”

More important than what she lost, she says, is what she’s gained: RitaSerrano is another step closer to fulfilling her lifelong vision – to be a professional boxer. It’s a dream shared by millions of young athletes, but Serrano is not one of them. She is 30, years beyond the age when trainers first start chiseling abs and carving muscles; she has a husband and four kids waiting for her at home; and, of course, she is not a man.

These obstacles, though, have only powered her determination, she says.

“I’ve waited my whole life to do this,” she says as she equipment-surfs at Phil’s, working her lean, muscular legs on this machine, her abs on that one. “I was always told, ‘Boxing’s not for girls’ or ‘You’ve got a family’ or ‘You’re too old to start doing this now.’ But now I’ve got a chance to prove to myself that I can do it. Better believe I’m going to try.”

*

Female boxers are becoming less of a rarity these days. Muhammad Ali’s daughter, Laila, boxes professionally. So do the daughters of boxing legends Joe Frazier and George Foreman. But even Christy Martin, one of the nation’s top female boxers with a 42-2-2 record and 31 knockouts, pulled in a mere $100,000 for her last fight, a fraction of the millions most big-name male boxers receive.

RitaSerrano knows it is still a male-dominated sport. She knew it on Feb. 24, when she looked up and realized she was one of only a few women at Will Rogers complex’s John Justin Arena waiting for her Golden Gloves fight. She knows it when she see newcomers to Phil’s Fitness Factory raise their eyebrows when she’s in the ring. She knows it when people ask her what she does in her spare time, and she replies, “box.”

Yet the tide is turning.

“It’s coming up now for women,” says Serrano. “You can see them on TV before the men’s matches. You hear all these famous names now. We’re getting the same amount of respect as male boxers. It’s not just about the men anymore.”

With more women being accepted into the sport, and her oldest son, Michael, turning the baby sitter age of 15, she figured the time and atmosphere were perfect for her to give boxing a shot; she has even quit her day job as a phlebotomist so she can work out and train every day.

Her real break came, she says, the day she met Henry Mendez.

In a sport that puts a premium on youth, this 30-year-old mother of four was worried she might not get her shot. “But Henry doesn’t think like that,” she says. “He thinks I can go all the way. I never had anybody like Henry before, so I never had that confidence.”

And if Mendez didn’t believe in her, he’d be the last person to encourage her.

“It’s a hard sport to be in. I told her, ‘You’re entering a man’s sport, and I’m going to train you and treat you like a man,’ ” says Mendez, 64, who has been working with Serrano for the last six months. “She doesn’t mind the training and the sacrifices and being tired or hurting. She’s a strong person. If she wants, she has the potential to go pro.”

She’s off to a good start: Serrano won her Feb. 24 fight at John Justin, advancing to a Golden Gloves boxing tournament on Saturday at the Diamond Hill Recreation Center; she’ll fight for a Fort Worth-based team against Dallas-based fighters. Two weeks before the battle at John Justin, she broke the nose of a sparring partner.

“She’s tougher than a lot of people I’ve trained,” Mendez says. “Even though she’s just an amateur, I train her like a professional. She’s made a decision to do this at an older age, when a lot of other fighters start at 16 or 17, and she’s made a lot of sacrifices. I think that’s made her tougher and more determined to succeed.”

“That’s what I get out of this,” Serrano says. “When I’m in the ring, it’s the feeling that I’m able to beat somebody way younger than me that satisfies me the most, the feeling that I still have it in me, that I can still knock out younger girls, that I can do anything younger fighters can, and do it even better.”

*

On a recent Sunday afternoon, the Serrano family is gathered around a big-screen TV watching Lady and the Tramp II. Rita‘s 3-year-old daughter, Victoria, runs around the family’s house in Crowley, playing with a kitten and a dog named Rocky. “Every dog I’ve ever had is named Rocky,” Rita says. “I’ve loved boxing all my life.”

Sons Michael, a boxer himself for two years before he turned his interests toward soccer, and Jonathan, 9, and David, 11, stroll in and out of the house, teetering between watching the movie and taking advantage of the warm March sun. Rita‘s husband of nearly 10 years, Jacob, a 34-year-old industrial electrician, sits on the couch, keeping one eye on the movie screen, the other on the kids. He hardly notices his wife is doing an interview. Like the rest of the family, he is getting used to Rita‘s burgeoning career. He even has a great sense of humor about it.

“I’m going to worry every time she steps into a ring, but we’re all going to support her, too,” says Jacob, who often tags along with Ritawhen she works out. “Heck, better her than me.”

Jacob, physically fit himself, spars with his wife on weekends. “I’m left-handed, and she’s not used to fighting left-handed, so it gives her good training,” he says.

Rita says it was another family member who supplied her with most of her training: her brother, Victor Jr., who, like their father, boxed in Golden Gloves competitions.

“[My brother] used to beat up on me to teach me self-defense,” she says. “[He] was always putting the gloves on me.”

Her parents, however, were always taking them off.

“They tried to stick me in ballet and tap. I was always kind of a daddy’s girl growing up. I wanted to take karate, but they wouldn’t let me. They just didn’t want me to get hurt.”

After living on Fort Worth’s north side, Serrano, then 9, moved to Crowley when her parents divorced. Her parents are still good friends, she says, and, perhaps through gritted teeth, they support her efforts in the ring.

“They’re finally accepting it. At first they didn’t want to, but once they saw I wasn’t going to back down, they started supporting me,” she says. “But they’re on pins and needles all the time.”

Serrano says she’s hoping her daughter, Victoria, will inherit her interest in boxing. “I’d love to put her in it,” she says. “That’s one of my goals, to get her into this. She’s got her mother and three brothers behind her. We all rough her up. She’ll be able to handle it.”

Last week, when Serrano looked into the eyes of a 12-year-old girl watching her practice at the gym, she saw Victoria.

“Ever since that little girl saw me working out, she’s wanted to be a fighter like me,” she says. “If I had that kind of inspiration when I was little, things might be a little different. Hopefully, that’ll be Victoria in a few years. This little girl even got against the wall with me for that exercise and she was like, ‘God, how do you do this?’ I said, ‘It ain’t easy. You’ve got to love it.’ “