Text:

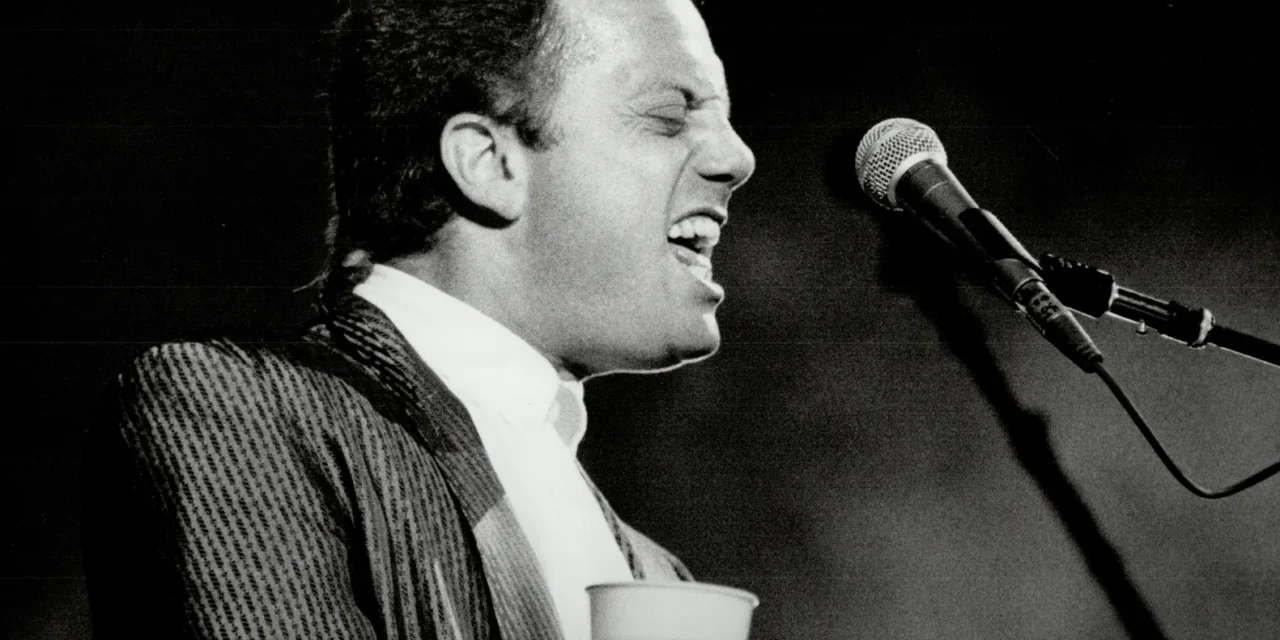

At 50, Billy Joel – one of the most important and prolific songwriters in pop music – is ending one phase of his career and beginning another.

Joel’s current tour, he promises, will be the last of its kind. After this, the Long Island-born pianist will immerse himself in writing (and possibly recording) classical music. On the phone from Houston, Joel looks back at his 20-year-plus career and ponders the future:

Q: You’ve been playing pop music all your life. Won’t it be weird not doing it?

A: Uh-uh. I did it. I’ve been on the road since I was 21. I’ve been in bands since I was 14. Now I’m 50. Some people have said, ‘You’re gonna go crazy.’ I took seven months off once and I did not go crazy. What I did was compose, what I’ve always been doing, but now I’m composing without a tour in mind. I’d like to walk away before I get kicked out, and, I’m sorry, but some people should get kicked out.

The great thing about rock ‘n’ roll is that it represents hormonal expressions of younger people, rage and joy. Rock didn’t come from a bunch of old farts playing the same song over and over. It’s like being an athlete, you’ve had your day, it was a good game, so maybe it’s time to coach or write a book about it. Make room for the newer people.

Q: How have you changed over the years and how have you stayed the same?

A: I thought that when I turned 50, I’d start falling apart and selling insurance. But I’m young at heart. Thank God I picked rock ‘n’ roll as a job ’cause it keeps ya young. So I’ve stayed the same in that respect.

How I have changed? I’ve been married and divorced twice. My daughter being born, that changed my life. My needs as an artist have changed. Pop music has a strict orthodox to it. You can’t be too complicated. You can be experimental, but you can’t be too musical. I needed to branch out. I see it happening with a lot of other people like me – Paul Simon, Sting, Bruce Springsteen. We don’t want our feet stuck in clay. I always go back to this great Dylan lyric, “He who is not busy learning is busy dying.”

Q: Since you have so many hits, do you feel pressure to deliver greatest-hits shows? Ever wish you could play a bunch of obscure stuff?

A: I like the odscure stuff, but every time we try to do something obscure, the audience is like ‘OK, thanks, next!’ Way out in the vast stretches of the nosebleed section, someone’ll yell, “Yeah!” But the majority of people are not familiar with those songs. You spent your money, you schlepped through the parking lot, you bought a crummy T-shirt that’s gonna fall apart and you’re sitting next to someone’s who’s smoking pot and throwing up all over you and then, what, I’m gonna start playing a bunch of songs you’ve never heard? I’d get pissed.

Q: A career high point?

A: When I made The Nylon Curtain, which I consider my masterpiece. And when we played what was still the Soviet Union, back in the ’80s. They went crazy. I don’t think they gave a damn who it was. We had a huge PA system, lights and staging, and we blew their heads off. And I’m not exactly Nine Inch Nails, you know, we played some ballads. But someone came up to me and said that this was the most important event there since the Russian Revolution.

Q: Does it bother you that some of your most popular work – like say Uptown Girl – has overshadowed your best work?

A: I think about that all the time. But when I write, I just write. Once in a while, I write something that’s an obvious hit, a jellybean I like to call them, and the record company goes, ‘Oh, goody, goody.’ It’s easy for them to digest. But if I only knew Billy Joel from his singles, I wouldn’t like the guy. Thing is, my songs were written to be placed next to other songs on an album. My albums are like little musicals. Uptown Girl made sense in context of that album, An Innocent Man, which was a tribute to R&B of the ’50s and ’60s; the people who do know the other songs have remained loyal to what we do.

Q: When you play some songs live, like Just the Way You Are, are you thinking about what you were thinking about the day you wrote them, or have they taken on new meaning over time?

A: Before a show, I can’t eat anything. You’re supposed to go onstage hungry. So when I’m singing that, I’m thinking, ‘Don’t go changing,’ hmmm, maybe I’ll get a club sandwich, “to try and please me,” no, but the fries will be too soggy, and I’d end up losing concentration, so we put that song away for a while. That was about ex No. 1. And then I got another divorce and who the hell wants to sing about her? But we’re back to playing those songs and I go back to that original emotion and what I do is, I’ll see a face in the crowd and I’ll connect them with that lyric.

Q: How do you want to be remembered?

A: I would like to be remembered as a writer. Rock star, that has no meaning to me. Writing is the hard part, and it’s the most satisfying thing for me. But once I heard Beethoven, it made me realize how insignificant I am.

Originally published Dec. 17, 1999