In the 1960s, Fort Worth had a vibrant garage rock scene but it wasn’t really brought to light until years later, when a couple local music aficionados started collecting those records. One of my absolute favorite stories that I wrote during my time at the Star-Telegram, this piece tells several different stories at once, from the release of this three-CD set to a look at what happened to some of the bands that made these great records.

Text:

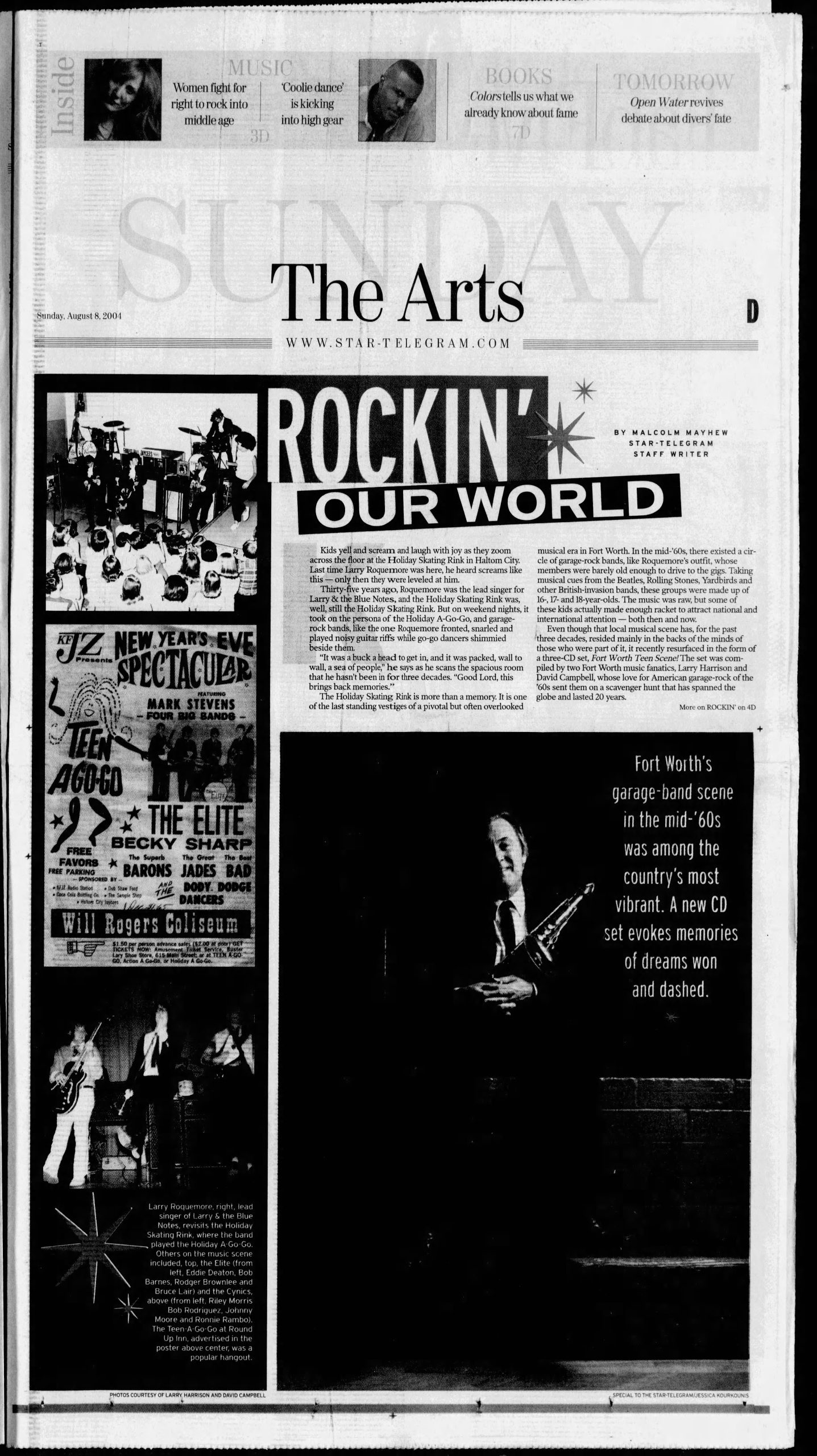

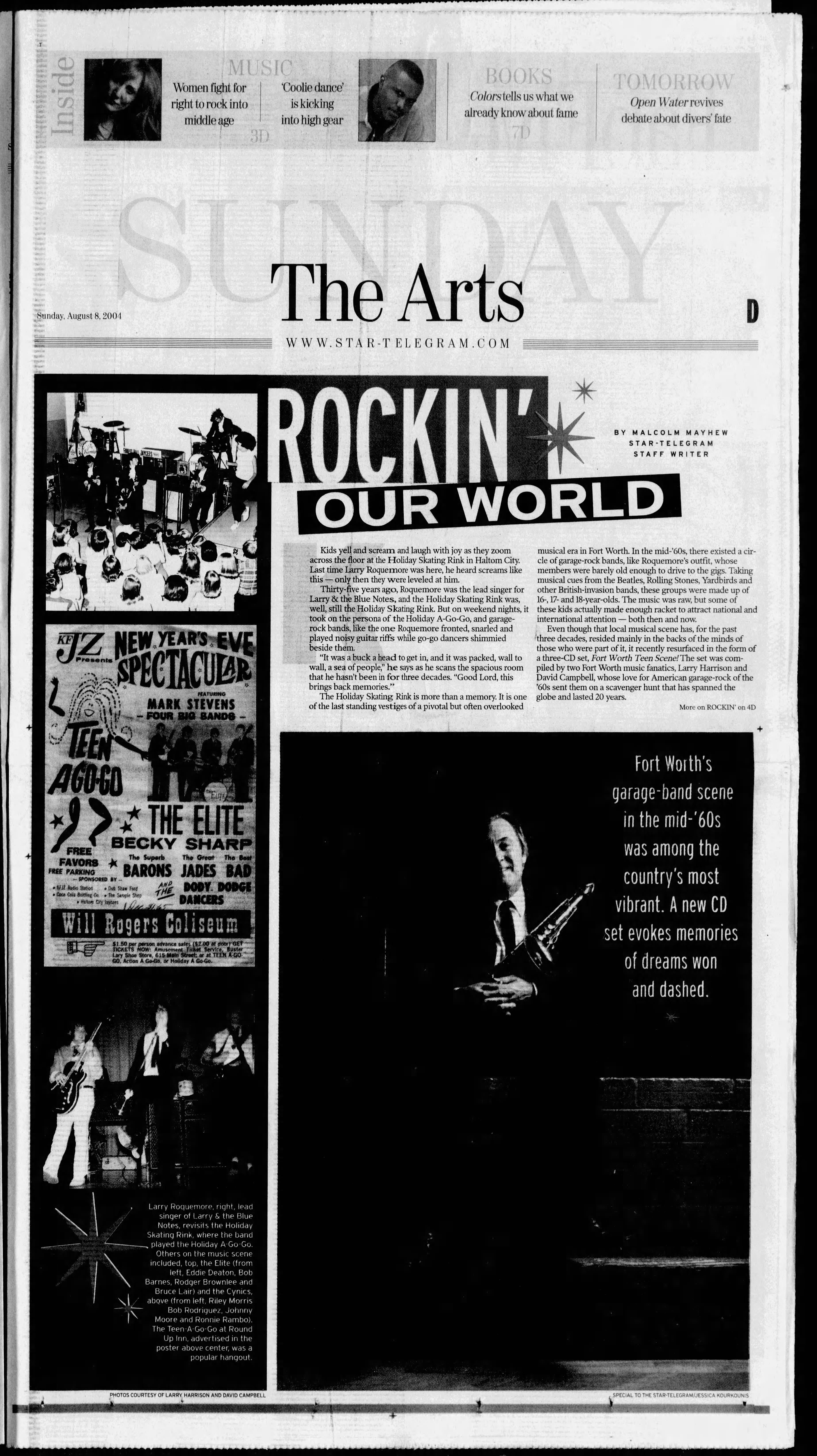

HALTOM CITY – Kids yell and scream and laugh with joy as they zoom across the floor at the Holiday Skating Rink in Haltom City. Last time Larry Roquemore was here, he heard screams like this — only then they were leveled at him.

Thirty-five years ago, Roquemore was the lead singer for Larry & the Blue Notes, and the Holiday Skating Rink was, well, still the Holiday Skating Rink. But on weekend nights, it took on the persona of the Holiday A-Go-Go, and garage-rock bands, like the one Roquemore fronted, snarled and played noisy guitar riffs while go-go dancers shimmied beside them.

“It was a buck a head to get in, and it was packed, wall to wall, a sea of people,” he says as he scans the spacious room that he hasn’t been in for three decades. “Good Lord, this brings back memories.”

The Holiday Skating Rink is more than a memory. It is one of the last standing vestiges of a pivotal but often overlooked musical era in Fort Worth. In the mid-’60s, there existed a circle of garage-rock bands, like Roquemore’s outfit, whose members were barely old enough to drive to the gigs. Taking musical cues from the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Yardbirds and other British-invasion bands, these groups were made up of 16-, 17- and 18-year-olds. The music was raw, but some of these kids actually made enough racket to attract national and international attention — both then and now.

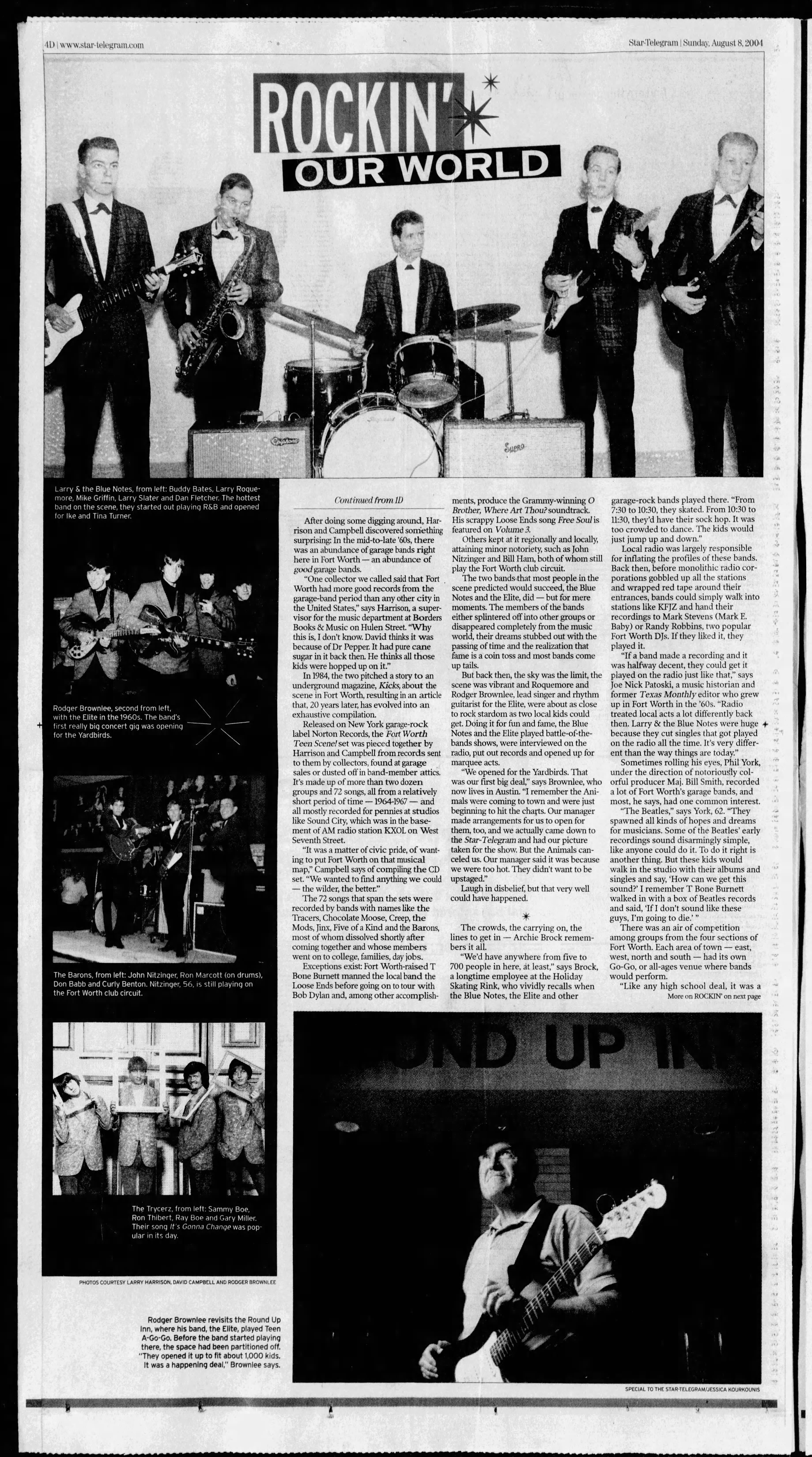

Even though that local musical scene has, for the past three decades, resided mainly in the backs of the minds of those who were part of it, it recently resurfaced in the form of a three-CD set, Fort Worth Teen Scene! The set was compiled by two Fort Worth music fanatics, Larry Harrison and David Campbell, whose love for American garage-rock of the ’60s sent them on a scavenger hunt that has spanned the globe and lasted 20 years.

“One collector we called said that Fort Worth had more good records from the garage-band period than any other city in the United States,” says Harrison, a supervisor for the music department at Borders Books & Music on Hulen Street. “Why this is, I don’t know. David thinks it was because of Dr Pepper. It had pure cane sugar in it back then. He thinks all those kids were hopped up on it.”

In 1984, the two pitched a story to an underground magazine, Kicks, about the scene in Fort Worth, resulting in an article that, 20 years later, has evolved into an exhaustive compilation.

Released on New York garage-rock label Norton Records, the Fort Worth Teen Scene! set was pieced together by Harrison and Campbell from records sent to them by collectors, found at garage sales or dusted off in band-member attics. It’s made up of more than two dozen groups and 72 songs, all from a relatively short period of time — 1964-1967 — and all mostly recorded for pennies at studios like Sound City, which was in the basement of AM radio station KXOL on West Seventh Street.

“It was a matter of civic pride, of wanting to put Fort Worth on that musical map,” Campbell says of compiling the CD set. “We wanted to find anything we could — the wilder, the better.”

The 72 songs that span the sets were recorded by bands with names like the Tracers, Chocolate Moose, Creep, the Mods, Jinx, Five of a Kind and the Barons, most of whom dissolved shortly after coming together and whose members went on to college, families, day jobs.

Exceptions exist: Fort Worth-raised T Bone Burnett manned the local band the Loose Ends before going on to tour with Bob Dylan and, among other accomplishments, produce the Grammy-winning O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack. His scrappy Loose Ends song Free Soul is featured on Volume 3.

Others kept at it regionally and locally, attaining minor notoriety, such as John Nitzinger and Bill Ham, both of whom still play the Fort Worth club circuit.

The two bands that most people in the scene predicted would succeed, the Blue Notes and the Elite, did — but for mere moments. The members of the bands either splintered off into other groups or disappeared completely from the music world, their dreams stubbed out with the passing of time and the realization that fame is a coin toss and most bands come up tails.

But back then, the sky was the limit, the scene was vibrant and Roquemore and Rodger Brownlee, lead singer and rhythm guitarist for the Elite, were about as close to rock stardom as two local kids could get. Doing it for fun and fame, the Blue Notes and the Elite played battle-of-the-bands shows, were interviewed on the radio, put out records and opened up for marquee acts.

“We opened for the Yardbirds. That was our first big deal,” says Brownlee, who now lives in Austin. “I remember the Animals were coming to town and were just beginning to hit the charts. Our manager made arrangements for us to open for them, too, and we actually came down to the Star-Telegram and had our picture taken for the show. But the Animals canceled us. Our manager said it was because we were too hot. They didn’t want to be upstaged.”

Laugh in disbelief, but that very well could have happened.

*

The crowds, the carrying on, the lines to get in — Archie Brock remembers it all.

“We’d have anywhere from five to 700 people in here, at least,” says Brock, a longtime employee at the Holiday Skating Rink, who vividly recalls when the Blue Notes, the Elite and other garage-rock bands played there. “From 7:30 to 10:30, they skated. From 10:30 to 11:30, they’d have their sock hop. It was too crowded to dance. The kids would just jump up and down.”

Local radio was largely responsible for inflating the profiles of these bands. Back then, before monolithic radio corporations gobbled up all the stations and wrapped red tape around their entrances, bands could simply walk into stations like KFJZ and hand their recordings to Mark Stevens (Mark E. Baby) or Randy Robbins, two popular Fort Worth DJs. If they liked it, they played it.

“If a band made a recording and it was halfway decent, they could get it played on the radio just like that,” says Joe Nick Patoski, a music historian and former Texas Monthly editor who grew up in Fort Worth in the ’60s. “Radio treated local acts a lot differently back then. Larry & the Blue Notes were huge because they cut singles that got played on the radio all the time. It’s very different than the way things are today.”

Sometimes rolling his eyes, Phil York, under the direction of notoriously colorful producer Maj. Bill Smith, recorded a lot of Fort Worth’s garage bands, and most, he says, had one common interest.

“The Beatles,” says York, 62. “They spawned all kinds of hopes and dreams for musicians. Some of the Beatles’ early recordings sound disarmingly simple, like anyone could do it. To do it right is another thing. But these kids would walk in the studio with their albums and singles and say, ‘How can we get this sound?’ I remember T Bone Burnett walked in with a box of Beatles records and said, ‘If I don’t sound like these guys, I’m going to die.’ “

There was an air of competition among groups from the four sections of Fort Worth. Each area of town — east, west, north and south — had its own Go-Go, or all-ages venue where bands would perform.

“Like any high school deal, it was a popularity contest,” says Nitzinger, now 56. “Your part of town was where you were the most popular. You go to another part of town, the band from that part of town was the most popular, which means there was always a little sense of danger. No fisticuffs, but there were damn sure the egos and the one-upmanship — who had the newest boots, the better-looking jacket? It was a trip.”

On top of this commotion and competition were Roquemore’s and Brownlee’s bands.

“It was pretty heavy stuff for a teen-ager,” Brownlee, 58, says. “I was 19, and the other three guys in my band were 17. We thought we were going to be the Beatles. We were young and very enthusiastic, and there was some talent there as well. We envisioned going on to bigger and better things.”

For a while, those visions seemed to be coming into focus. Formed in 1964, the Elite cut four records, opened up for the Beach Boys and Paul Revere and the Raiders, were featured in the national music magazine Record World and even had some international radio airplay.

“We started out playing frat parties, sleepovers and slumber parties, until we got an audition with Mark E. Baby,” Brownlee says of the DJ and concert promoter. “He was the biggest DJ in town, and he said, ‘I want you to be in my circuit.’ He said, ‘I’ll start you off at the Holiday, and when you get as good as Larry & the Blue Notes, we’ll pay you $12 a night.’ He started us off at $7. Our debut was at the Holiday.”

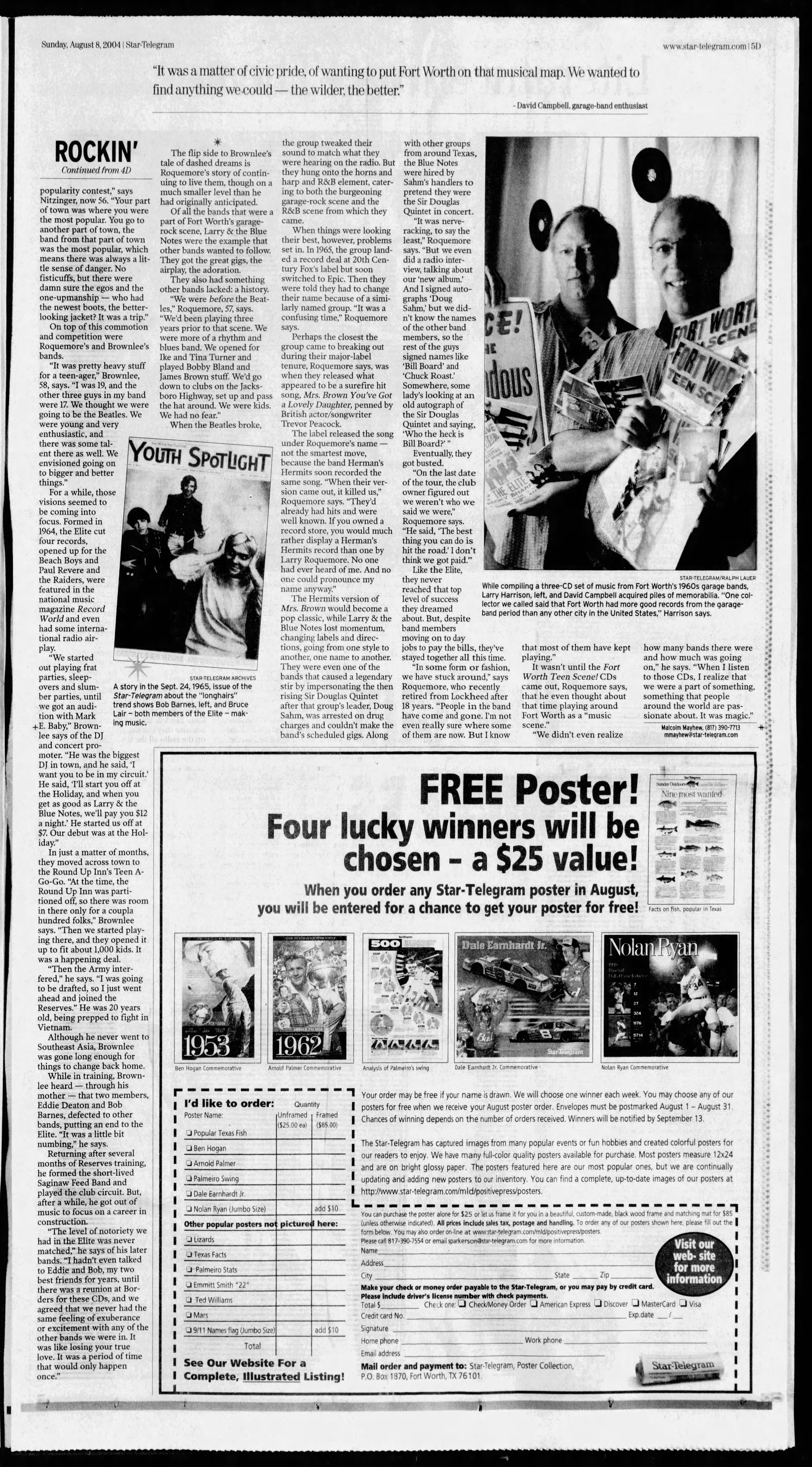

In just a matter of months, they moved across town to the Round Up Inn’s Teen A-Go-Go. “At the time, the Round Up Inn was partitioned off, so there was room in there only for a coupla hundred folks,” Brownlee says. “Then we started playing there, and they opened it up to fit about 1,000 kids. It was a happening deal.

“Then the Army interfered,” he says. “I was going to be drafted, so I just went ahead and joined the Reserves.” He was 20 years old, being prepped to fight in Vietnam.

Although he never went to Southeast Asia, Brownlee was gone long enough for things to change back home.

While in training, Brownlee heard — through his mother — that two members, Eddie Deaton and Bob Barnes, defected to other bands, putting an end to the Elite. “It was a little bit numbing,” he says.

Returning after several months of Reserves training, he formed the short-lived Saginaw Feed Band and played the club circuit. But, after a while, he got out of music to focus on a career in construction.

“The level of notoriety we had in the Elite was never matched,” he says of his later bands. “I hadn’t even talked to Eddie and Bob, my two best friends for years, until there was a reunion at Borders for these CDs, and we agreed that we never had the same feeling of exuberance or excitement with any of the other bands we were in. It was like losing your true love. It was a period of time that would only happen once.”

*

The flip side to Brownlee’s tale of dashed dreams is Roquemore’s story of continuing to live them, though on a much smaller level than he had originally anticipated.

Of all the bands that were a part of Fort Worth’s garage-rock scene, Larry & the Blue Notes were the example that other bands wanted to follow. They got the great gigs, the airplay, the adoration.

They also had something other bands lacked: a history.

“We were before the Beatles,” Roquemore, 57, says. “We’d been playing three years prior to that scene. We were more of a rhythm and blues band. We opened for Ike and Tina Turner and played Bobby Bland and James Brown stuff. We’d go down to clubs on the Jacksboro Highway, set up and pass the hat around. We were kids. We had no fear.”

When the Beatles broke, the group tweaked their sound to match what they were hearing on the radio. But they hung onto the horns and harp and R&B element, catering to both the burgeoning garage-rock scene and the R&B scene from which they came.

When things were looking their best, however, problems set in. In 1965, the group landed a record deal at 20th Century Fox’s label but soon switched to Epic. Then they were told they had to change their name because of a similarly named group. “It was a confusing time,” Roquemore says.

Perhaps the closest the group came to breaking out during their major-label tenure, Roquemore says, was when they released what appeared to be a surefire hit song, Mrs. Brown You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter, penned by British actor/songwriter Trevor Peacock.

The label released the song under Roquemore’s name — not the smartest move, because the band Herman’s Hermits soon recorded the same song. “When their version came out, it killed us,” Roquemore says. “They’d already had hits and were well known. If you owned a record store, you would much rather display a Herman’s Hermits record than one by Larry Roquemore. No one had ever heard of me. And no one could pronounce my name anyway.”

The Hermits’ version of Mrs. Brown would become a pop classic, while Larry & the Blue Notes lost momentum, changing labels and directions, going from one style to another, one name to another. They were even one of the bands that caused a legendary stir by impersonating the then rising Sir Douglas Quintet after that group’s leader, Doug Sahm, was arrested on drug charges and couldn’t make the band’s scheduled gigs. Along with other groups from around Texas, the Blue Notes were hired by Sahm’s handlers to pretend they were the Sir Douglas Quintet in concert.

“It was nerve-racking, to say the least,” Roquemore says. “But we even did a radio interview, talking about our ‘new album.’ And I signed autographs ‘Doug Sahm,’ but we didn’t know the names of the other band members, so the rest of the guys signed names like ‘Bill Board’ and ‘Chuck Roast.’ Somewhere, some lady’s looking at an old autograph of the Sir Douglas Quintet and saying, ‘Who the heck is Bill Board?’ “

Eventually, they got busted.

“On the last date of the tour, the club owner figured out we weren’t who we said we were,” Roquemore says. “He said, ‘The best thing you can do is hit the road.’ I don’t think we got paid.”

Like the Elite, they never reached that top level of success they dreamed about. But, despite band members moving on to day jobs to pay the bills, they’ve stayed together all this time.

“In some form or fashion, we have stuck around,” says Roquemore, who recently retired from Lockheed after 18 years. “People in the band have come and gone. I’m not even really sure where some of them are now. But I know that most of them have kept playing.”

It wasn’t until the Fort Worth Teen Scene! CDs came out, Roquemore says, that he even thought about that time playing around Fort Worth as a “music scene.”

“We didn’t even realize how many bands there were and how much was going on,” he says. “When I listen to those CDs, I realize that we were a part of something, something that people around the world are passionate about. It was magic.”