Originally published March 25, 2007

Text:

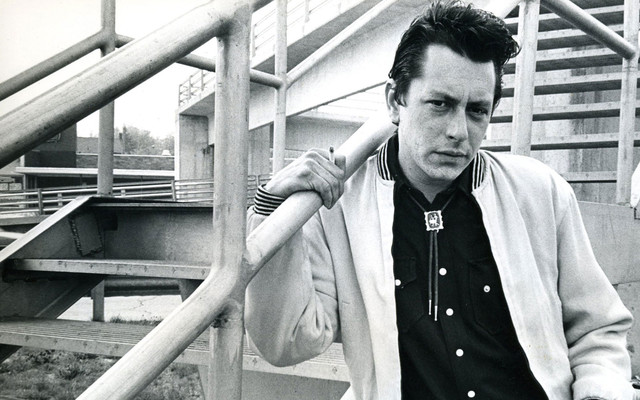

When Texas musician Joe Ely was a kid, about 7 years old, he caught what he describes as “borderline rheumatic fever.” It forced him to stay home from school for months, bedridden.

But even then, Ely says, he was on the road. Trapped in bed, he built his own world of roads and intersections and things whirling by in a windshield blur, and he stashed them away in his imagination. He’d travel them, he says, so he wouldn’t go stir-crazy.

“I made places up,” Ely says by phone from the Denver airport. “I made up these extravagant destinations and these long roads I took to get there. It was an awful time in my life, being in bed all the time, and being sick and not being able to move. If it wasn’t for my imagination, I’m not sure how I would have gotten through that.”

In a way, that was Ely’s first taste of what was to come: cityscapes coming into focus, then fading in the rearview; small towns filled with colorful characters; miles and miles of railroad tracks; car wheels on a gravel road.

For the past four decades, Joe Ely has made a living out of traveling these roads and documenting what he has seen, done, run away from and come home to. His music is soaked in metaphors about the road and filled with restless characters who long to hit the highway and never look back, or with melancholy sentimentalists who can’t wait to sleep in their own bed again.

At age 60, Ely is still coasting down these roads, at his own pace. In the past few weeks, he has released three projects: two new albums of old songs, Happy Songs From Rattlesnake Gulch and Silver City (Pearls From the Vault Vol. 1), and a book of his road journals, Bonfire of Roadmaps (an exhibit of Ely-penned drawings and sketches from Bonfire is on display at the University of Texas at Austin). He released the CDs on his own dime and time, eliminating the middlemen who once stood in his way, like potholes and stop signs.

“Whether he’s jumping trains and going all over the country or putting out his own records, there’s just no stopping Joe when he gets his mind set on something,” says Davis McLarty, who for several years played drums in one of Ely’s many bands. “There never has been.”

You don’t know Joe

To try to fully tell the tale of Joe Ely’s life is a fruitless task. Every album he has released, every oddball experience he has had, everyone he’s jammed with, opened up for, got in a fight with or shared drinks with, is the equivalent of a short novel. There’s simply not enough paper or time to document all of his you-would-never-believe-what-happened-to-me tales.

But the Amarillo-born/Lubbock-raised singer has tried. Go to his Web site, www.joeely.com, and you’ll see one of the most unusual things you’ll ever find on an artist’s site: a frequently-asked-questions guide. There, the many myths swirling around Ely’s life are confirmed.

Yes, he really did ride a motorcycle down the hall of Monterey High School in Lubbock — on the first day of school. But that’s not what got him expelled. He was tossed, according to the site, for singing Cherry Pie at a school assembly.

Yes, he really did play the old Cellar club in Fort Worth, alternating shifts with an early incarnation of ZZ Top.

Yes, he really did move to New York with visual artist Jim Franklin to help him paint a mural for the original production of Stomp. And, yes, he really did wind up joining Stomp as a musician.

Yes, he really did join the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus in 1974. He took care of the llamas and was kicked unconscious by a horse.

Yes, he really did befriend and jam with the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Chuck Berry and the Clash. He struck up a particularly strong relationship with the members of the Clash. They even visited him in Lubbock; a year later, Ely went out on the road with the band, as they supported their seminal album, London Calling. They played everywhere from Dallas to England.

“And the funny thing is, that doesn’t even scratch the surface,” says longtime friend Jimmie Dale Gilmore, who plays with Ely in the country-rock band the Flatlanders. Every day is some new adventure, and there’s just no way to tell all his stories.

But again, Ely has tried. On every one of his 14 studio albums, Ely has incorporated some aspect of his ever-twisting life — the famous people he has met, the down-on-the-luckers he has befriended, the people who fall through the cracks of life and those who strut on top of them.

“That’s always been my focus — the song,” he says. “To me, a song is a story distilled into three minutes. And I guess that’s what kept me going all this time — this need to find those stories, those songs, wherever they’re hiding. And I carry those songs with me, from city to city. It’s the only thing that I have. I guess they’re all just combinations of the good and bad decisions I’ve made in life, all rolled up into one.”

Thanks for the memories

Many of those stories have all been rolled up into one new book, Bonfire of Roadmaps (University of Texas Press, $19.95), a collection of diarylike journals that Ely starting keeping in the early 1970s.

“I never intended for anyone to read these,” he says. “They were just private notes. I wasn’t real interested in letting them out. But then I realized, after rereading some of them, that some of the stories had real beginnings and endings and read like real stories. I figured that if I had enough sections like that, that maybe there was a book there. People kept telling me, ‘You need to write a book,’ so I guess I did without even really knowing it.”

A good chunk of his notes are missing, however. His stories from 1975-1980 drove away in a New York City cab. He pleaded with the public for their return, but they never showed up.

“That was pretty devastating,” he says. “I’m not even really sure why anyone would want them. They were just random thoughts and notes that meant nothing to anyone but me.”

Bonfire of Roadmaps led to two new albums. Or, rather, two new albums of old material, Happy Songs From Rattlesnake Gulch and Silver City (Pearls From the Vault Vol. 1). Both are collections of revamped, reworked songs that Ely either started and never completed, or just forgot about.

“When I was going through my journals to work on the book, I discovered all these notes that reminded me of certain songs,” he says. “Some were just in pieces. Some were just beginnings. But I took those tracks and rewrote them, and built on their original foundations, and it became this fun little project.” That’s how Happy Songs From Rattlesnake Gulch was born.

“Then I discovered a whole bunch of songs in the bottom of an old suitcase that I’d written in the 1960s,” he says. “They’re almost folk songs. They were written at a time when I was traveling around, jumping trains and stuff. I never recorded any of those, either.” Thus was born Silver City.

“I figured that it’d be a good idea to put out the records with the book, sort of like a soundtrack for the book,” he says. “Then I came to the realization that no record company would want to do that — put out two records at once. They’d think it was complete lunacy. Most labels want you to wait a year, a year and a half between releases these days. So I just got hardheaded and, not having any good sense, started my own record company so I could put them out myself and not have to worry about what anyone else thinks.”

Since the beginning of the year, Ely has been on tour supporting the releases. Later this year, he wants to do some performances in which he both reads and sings. He’s doing a show like that soon in Austin, and he’s hoping to do one in Fort Worth, possibly at a Borders bookstore. If those go well, he’ll do a string of such performances, he says.

“I’ve never done anything like this before,” he says. “I’m always trying to find new ways to challenge myself and present my material in different ways. This way, I could share a lot of stories that I really don’t have time to share when I’m playing a traditional concert. And if there’s one thing I have, it’s a lot of stories.”

A man of many hats

There is Joe Ely, the musician: the man who has influenced Texas music and beyond, the man who has played in dozens of bands since high school; the man who has bravely mixed rock with country with flamenco with folk with Tejano; the man who tours for months and months on end, by himself, with his old pals in the Flatlanders or with his old band mates from the ’70s.

There is Joe Ely, the adventure-seeker: the man who used to jump trains for the heck of it; then, the railroad became more than a lark. It became his means of transportation, his way of getting from one gig to another, one crummy job to another.

“My dad died when I was 13, so I became the sole breadwinner for the family,” he says. “I worked after school, washing dishes, doing whatever, just these terrible jobs. I started playing honky-tonks on the outskirts of Lubbock, but then I started playing in other cities, and sometimes jumping a train was the only way to get there.

“I remember this one time, I thought I jumped a train that was going to New Mexico, and I wound up in the desert in Nevada,” he says. “It’s not an exact science, by any stretch of the imagination.”

And then there is Joe Ely, the family man.

He has been married to the same woman, Sharon, for more than 20 years; they’ve known each other for 35. They have a daughter, Marie Elena Ely.

Sharon and Joe met in 1967, when Joe was performing at a coffeehouse in Lubbock. “He was a one-man band at the time and played harmonica, guitar and high-hat and sang, all at the same time,” Sharon says. “We laughed so much when we met. Before we lived together, I used to call and have him come over to fix my gas-burning icebox. Only a few people knew how to light the pilot, and it was a good excuse to see him.”

Sharon is one of the few anchors in Ely’s madly fluctuating life. She knew what she was getting into and has grown to equally appreciate his time with her and his time on the road.

“When Joe goes on the road, I travel with him sometimes, which is just great,” she says. “But sometimes I don’t go with him, and I am sometimes glad to get him out of my hair. There tends to be a constant whirlwind around him wherever he goes. But then by the time he comes back home, I’m so happy to see him. It’s such a magic balance, and I believe this is why we have been so close for so long and continue to be this way.”

At home, at their house outside of Austin, Sharon says, Ely is the direct opposite of how he is onstage.

“When he’s onstage, he screams and makes great noises and rocks out beyond anything imaginable,” she says. “Whereas at home he is quiet, thoughtful and very introverted. He’s kinda brilliant in that he just knows how to do technical things that I cannot figure out — solving computer glitches, repairing telephones and light-bulb problems.”

Music does factor into his home life, as it does every other aspect of his life.

Ely wrote an album for his daughter and gave it to her one Christmas.

“That’s just one of many albums the public has never heard,” he says. “I may release it someday. Doing my own label has opened my mind to what the process of making records is, and it’s not what I always thought it was, when someone else was selling it and marketing it.

“I want to make records now for my own satisfaction,” he says. “And maybe not even put them in record stores. Maybe just put them up on my Web site, or on iTunes. I have a bunch of things planned. I have at least 20 records of stuff that I wanna put out. So, in some ways, I feel like I’ve only just begun.”