Not sure what Henry Bogdan is doing these days, but in 1995, he was the bassist for Helmet, an early noise band whose abrasive music often got sidled with metal. I talked to Helmet several times over the years; this was probably the most entertaining of those interviews. Bogdan isn’t one to hold back.

Originally published Aug. 17, 1995

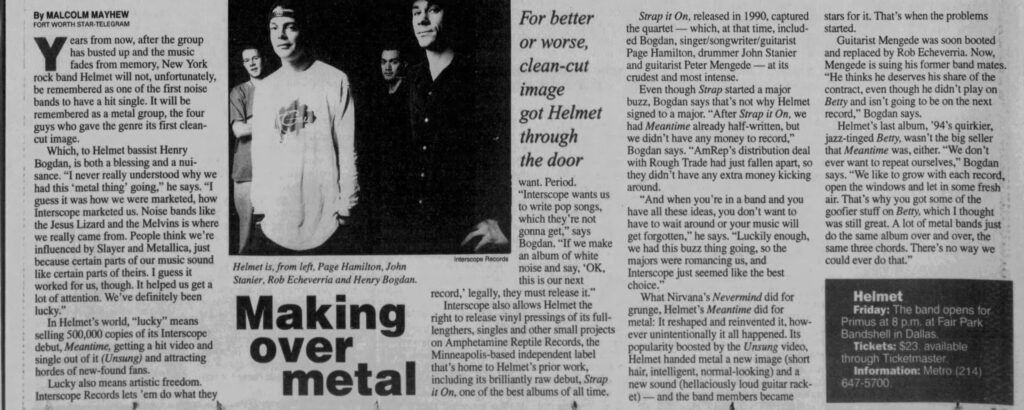

Years from now, after the group has busted up and the music fades from memory, New York rock band Helmet will not, unfortunately, be remembered as one of the first noise bands to have a hit single. It will be remembered as a metal group, the four guys who gave the genre its first clean-cut image.

Which, to Helmet bassist Henry Bogdan, is both a blessing and a nuisance. “I never really understood why we had this `metal thing’ going,” he says. “I guess it was how we were marketed, how Interscope marketed us. Noise bands like the Jesus Lizard and the Melvins is where we really came from. People think we’re influenced by Slayer and Metallica, just because certain parts of our music sound like certain parts of theirs. I guess it worked for us, though. It helped us get a lot of attention. We’ve definitely been lucky.”

In Helmet’s world, “lucky” means selling 500,000 copies of its Interscope debut, Meantime, getting a hit video and single out of it (Unsung) and attracting hordes of new-found fans.

Lucky also means artistic freedom. Interscope Records lets ’em do what they want. Period. “Interscope wants us to write pop songs, which they’re not gonna get,” says Bogdan, who was also the original drummer for Poison 13, another pioneering punk-noise band. “If we make an album of white noise and say, `OK, this is our next record,’ legally, they must release it.”

The band often pays its own way, though, footing the bill for overseas tours and extras, such as nice hotel rooms and decent meals. “Most of Interscope’s money goes to recording, making stupid videos and paying managers,” says Bogdan, 34. “Meantime sold all those copies, so we have the money to support ourselves. That’s important to us, too, not having to rely that much on the label.”

Interscope also allows Helmet the right to release vinyl pressings of its full-lengthers, singles and other small projects on Amphetamine Reptile Records, the Minneapolis-based independent label that’s home to Helmet’s prior work, including its brilliantly raw debut, Strap it On, one of the noise genre’s best albums of all time.

Strap it On, released in 1990, captured the quartet – which, at that time, included Bogdan, singer/songwriter/guitarist Page Hamilton, drummer John Stanier and bassist Peter Mengede – at its crudest and most intense. Not giving a flip about his voice, Hamilton gurgles, groans and painfully screams over and over, while the band agonizingly chugs through three-chord hell. For many bands that rose in Helmet’s wake, it’s an album so influential, they can’t help but cop it, yet so untouchable, there’s no getting near it.

Even though Strap started a major buzz, Bogdan says that’s not why Helmet signed to a major. “After Strap it On, we had Meantime already half-written, but we didn’t have any money to record,” Bogdan says. “AmRep’s distribution deal with Rough Trade had just fallen apart, so they didn’t have any extra money kicking around.

“And when you’re in a band and you have all these ideas, you don’t want to have to wait around or your music will get forgotten,” he says. “Luckily enough, we had this buzz thing going, so the majors were romancing us, and Interscope just seemed like the best choice.”

What Nirvana’s Nevermind did for grunge, Helmet’s Meantime did for metal: It reshaped and reinvented it, however unintentionally it all happened. Its popularity boosted by the Unsung video, Helmet handed metal a new image (short hair, intelligent, normal-looking) and a new sound (hellaciously loud guitar noise delivered in three-minute bites) – and the band members became stars for it. That’s when the problems started.

Guitarist Mengede was soon booted and replaced by Rob Echeverria. Now, Mengede is suing his former band mates. “He thinks he deserves his share of the contract, even though he didn’t play on Betty and isn’t going to be on the next record,” Bogdan says. “He wants as much money as possible, but the only people who are going to make money off this are the lawyers.”

Bogdan’s referring to Helmet’s last album, ’94’s quirkier, jazz-tinged Betty, wasn’t the big seller that Meantime was. “We don’t ever want to repeat ourselves,” he says. “We like to grow with each record, open the windows and let in some fresh air. That’s why you got some of the goofier stuff on Betty, which I thought was still great. A lot of metal bands just do the same album over and over, the same three chords. There’s no way we could ever do that.”