Pretty Darn Texan

Charlie Robison is a pure Texas music star – confident, intelligent, witty and in contrast to some country music celebrities, he still lives in Texas

By Malcolm Mayhew

A man in a dirty cowboy hat cuts a trail through Borders bookstore in San Antonio, garnering looks from the upscale suburbanites who’ve come to sip coffee, flip through magazines and let their freshly-scrubbed children ransack the kids’ area. Charlie Robison, it seems, is out of his element.

“I’m in this big truck with mud all over it,” he says over his cell phone, describing his ride, as if it’s not hilariously obvious that the dirt-caked F-250 rumbling in the parking lot, shaking the windows of all the BMWs and Chevy Suburbans, belongs to him. The dog rolling around in the truck’s bed, Robison warns, does indeed bite.

With his scuffed boots, Levi’s work jeans, dirty truck and potentially vicious dog, Robison blends into the crowd at this new stip mall about as much as one of the suburbanites would on one of Robison’s two ranches. But throughout our daylong conversation, which started in that parking lot, wound its way through the backroads of Texas’ picturesque Hill Country, then ended with the last sip of a beer in his hometown of Bandera, it seems that Charlie Robison is clearly a contradiction. He really does fit in at Borders, albeit reluctantly.

*

Three years ago, then-34-year-old Charlie Robison released his major label debut, Life of the Party. And there it sat in the CD bins, yet another record by a member of the Robison family to be hailed by critics but bought only by friends and followers. Life of the Party, at that point, was anything but. It mainly occupied shelf space between “McGraw, Tim” and “Twain, Shania.”

This was certainly nothing new to Robison. For years, he and his singer-songwriter brother Bruce Robison had languished in near-obscurity, playing honky-tonks in and around Austin for dimes and drinks. Besides, Robison already knew the music industry could be as domineering and vengeful as any jilted lover. Charlie’s sister-in-law, and Bruce’s wife, Austin songbird Kelly Willis – an angel with a devilish twang – had experienced the ups and downs of creating music for Nashville record companies.

Robison experienced his own challenges. He gritted his teeth and bit his lip when asked to clean up some of Party’s lyrics, which raised some eyebrows of executives at Lucky Dog Records, a label owned by Sony Music. “The label had a problem or two with some of the lyrics, so I changed them for radio. I expected that to happen,” he says. “We all have to make sacrifices. You give a little here, maybe you can take a little there.”

When it was released in the spring of 1998, Life of the Party received light airplay on Texas music specialty shows. As months went by, tracks such as “Sunset Boulevard,” “My Hometown” and “You’re Not the Best” slowly graduated from getting played once a week to once a day. Country Music Television put Robison over the top on a national level when it began airing the video for “My Hometown.” Nearly a year after its release, Life of the Party rose out of the discount bin and was plopped into the buzz bin. It charted in April 1999.

And the cool thing is, hardly anyone knew this guy is married to a Dixie Chick.

*

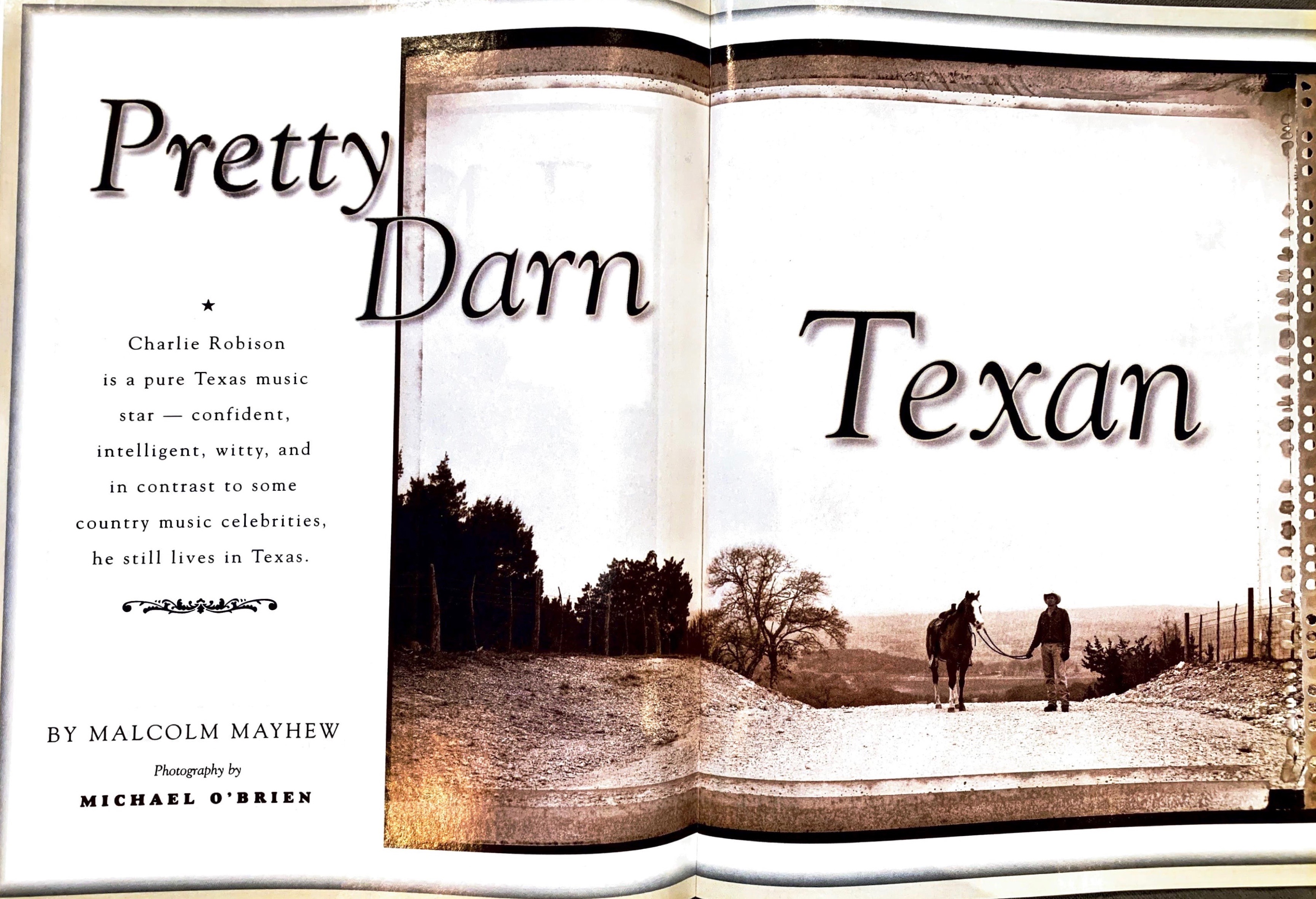

Standing on the edge of a riverbank, where he is surrounded by nature’s beauty and silence, Robison points to something in the distance. “That’s the Guadalupe River,” he says nonchalantly, as if it’s no big deal to have one of Texas’ most scenic rivers in your backyard.

It is a very big backyard. Robison won’t say how much land this ranch – one of two in his family – encompasses, but judging from the fact that there’s not a fence or another neighbor in sight, it is clearly a whole helluva lot. “Real ranchers don’t brag about how much land they own,” he says.

As he has been all his life, Robison is indeed a true rancher. Every day, he makes an hourlong trek from San Antonio, then veers off onto a small road that snakes through tree-lined hills and quivering prairies. The road turns into a rock trail one couldn’t tackle without a souped-up truck. This is where he and his cow-dog Buddy rustle up packs of cattle and, a few feet away, workers map out the foundation for a soon-to-be-built house, soon to be occupied by Robison and his wife Emily, the banjo player in Texas’ way famous Dixie Chicks.

The couple currently lives in San Antonio. Robison says that while San Antone is fine, he’s more at home out here, where he can be close to his main love: ranching. Emily’s gotten into it, too. “Oh, she loves it,” he says. “Only she keeps wanting to name the cows. I’m like, `Honey, please don’t name the cows.’ “

About an hour from here is the family ranch, a majestic slice of Texas land dotted with caves, rocky, rolling hills and the type of photographic scenery that attracts people to the Lone Star State, but is slowly being gobbled up by mini-malls and inevitable urbanization. There are no roads on this ranch, just avenues of white, choppy rocks that lead to the Robison house, a small, innocuous mound of bricks still occupied by Robison’s father, a divorced rancher. “He’s a workaholic,” he says. “I guess that’s where I get it.”

A stable of horses gets excited when they hear the rumbling of Robison’s oncoming truck. This is one of his other loves: caring for his prized horses. “One of these horses cost me more money than three of these trucks,” he says, apparently seriously. Trying out a new saddle, he takes one of the horses for a spin. And on this crisp, clear day, with miles of land to tend, horses to care for, cattle to rustle, barns to repair and other chores to get done, music is the furthest thing from Robison’s mind, as it often is.

*

Finding stuff to talk to Robison about is not at all difficult. Although he dropped out of college to pursue music full-time, he is well-educated in and obsessively passionate about a number of topics: Texas history, politics, the future of the farm and ranch industry, living in a small town vs. a big city and, of course, music. Throughout the day, he intelligently weaves these subjects together, binding them with the type of acidic humor that might offend you if you didn’t know him. He is especially infatuated with and exceptionally knowledgable about his family’s roots, which stretch back to the mid-1800s, when his German ancestors established the small Texas town of Comfort.

An old cemetery is the town’s subtle centerpiece. Robison’s grandparents are buried here, along with other relatives. A cigar hanging from his mouth, he stands over his grandmother’s grave, a smile slowly etching its way across his clean-shaven, plainly handsome face.

“She was a real character,” he says. “She laughed at everything. She went through a lot, but always come through wearing a smile. That’s how she dealt with a lot of tragedy, by finding even the slightest bit of humor in it. She’s definitely how I inherited my sense of humor.”

Unlike his brother Bruce, a quiet, gentle sentimentalist, Charlie coats his songs in layer upon layer of backhanded humor. It’s hard to tell when he’s being serious. “The Wedding Song,” a gorgeous duet with Dixie Chicks singer Natalie Maines and the standout track from his new CD, Step Right Up, is the perfect example of Charlie’s brainy but often misunderstood wit.

“I guess I still love you, if I ever did, and I could see myself having a couple of kids,” Robison sings, while Maines retorts, “I wasn’t prepared for the weight of this ring, but we will get by, for the rest of our lives.” It’s a sweet song with sour lyrics, one that will undoubtedly draw attention when it comes out in April.

“You can go either way with that song,” Robison says. “You can look at it as a love song about a couple that has stayed together through a lot of shit, or you can look at it as a story about a couple that married young and, as a result, missed a lot of chances to do something different with their lives. It’s not an autobiographical song, but it’s what happened to a lot of my friends. They married their high school sweethearts, got jobs, got pregnant and settled down. And that’s the only world they’ve ever known.”

Most of Robison’s songs have an autobiographical slant to them. They’re either about him or friends or family or people he knew growing up. The Robert Earl Keen-ish “Desperate Times,” a track about a guy who robs a bank but gets fingered by his girlfriend, was inspired by a guy Robison knew, a guy who’s either in jail now or just getting out.

“Can’t remember if he’s locked up or not but, yeah, that’s a true story,” he says, gliding down the highway toward Bandera, the latest CD by Slaid Cleaves playing on his truck’s stereo. “Those are the types of songs I like – real songs, songs about real people. That’s why I was never a big fan of Bob Dylan. His music was too metaphorical. I love Jackson Browne and, as far as new singers go, I like Slaid Vleaves and Adam Carroll, because they write but brilliant songs about everyday people and everyday things that you can relate to and see your reflection in. That’s the biggest compliment I can ask for, when someone comes up to me and says, “Hey, I can relate to “My Hometown.'”

As Robison finishes that thought, a roadside sign signaling Bandera’s city limits whizzes by, and that town that plays such a pertinent role in Robison’s life and music begins to grow in the horizon, building by building. “All you gotta do is step into Bandera, and you get song ideas galore,” he says. “Every person here has an interesting story to tell. If I want to get inspired, all I gotta do is go home.”

*

A small town about an hour west of San Antonio, Bandera (population 877) looks just like the sonic paintings Robert Earl Keen, the Robison’s and so many other Texas singer-songwriters have splashed across plastic canvases. Small, mom-and-pop restaurants line the streets. Texas and U.S. flags rustle in the wind. Townspeople quietly go about their business, nodding to one another. Some are coming home from their workday; others are on their way to bars. The main road that cuts through the downtown area is paved in mud-splattered trucks, like the one driven by Robison, who is clearly glad to be home.

In his hand are two photos – one of him and one of the Dixie Chicks. He carries them into a rustic barbecue joint, where other publicity photos of country singers line the walls like family portraits in someone’s living room. The women who work here know him immediately. Soon, he has a free beer in one hand, a saucy sandwich in the other. The pictures are tacked on the wall.

“It’s funny, you work your whole life so you can pay for things, and then you become famous and you don’t have to anymore,” he says. But Robison’s not cocky about his fame or the fame he is bound to by blood and marriage. He treats the waitresses here like he would his own family, with the kind of warmth that develops only through time. He talks shop with them, then winds up paying for the beer. If anything, Robison acts truly thankful for what he has. There was a time, he explains, when he had absolutely nothing.

“My family was dirt poor,” he says. “Our entertainment consisted of a radio. We were that poor.” It was that radio, however, that altered his life and the life of his brother, Bruce. “Jackson Browne – I heard him and said to myself, ‘This is someone who feels like me.’ Guys like him make you feel less like a weirdo if you don’t fit in, and I can’t say that I exactly fit in at high school. I still love to hear his old songs, there’s so much of a kinship there. I know it sounds stupid or whatever, but the closest sensation I can equate to hearing Browne’s Saturate Before Using the first time is finding religion. That’s how much of a shock it was to me.”

Music meant so much to Charlie that he jettisoned a football and baseball scholarship and dropped out of Southwest Texas State to move to Austin. Bruce, then attending and playing basketball for West Texas State, joined him, taking classes at Trinity Valley College in Austin.

The two formed separate bands. They kind of had to. “Charlie has his style and I have mine,” Bruce said in an earlier interview. “We were influenced by a lot of the same people, by a lot of the same bands, and we had our own bands. But we just grew in different directions musically. Let’s just say our music definitely reflects our personalities.”

To make the rent, Charlie had to take a series of day jobs. “Worst one? I was a waiter at a country club,” he says. “It was the worst job ever. But Austin wasn’t like it is now. Now every frat kid with a guitar has a gig. It wasn’t always like that. In other ways, living in Austin back then was great. You got free beer. You could live there on $300 a month. Now, you get ticketed for unloading your gear on the street.”

After a string of Charlie’s bands formed then dissolved, he set out on his own, developing a name for himself as a snidely smart songwriter and overwhelmingly entertaining performer. Bruce was carving out a niche of his own as a pensive, heartfelt lyricist. The two landed different degrees of success at nearly the same time. Bruce swung his current publishing deal with Carnival Music, and Charlie signed to major label Warner Brothers.

Warner wound up scribbling Charlie’s name off its roster, though, when he refused to cater and crater to Nashville’s then-burgeoning, Garth Brooks-inspired, hat-act scene. But enough talk had circulated in Nashville about the Robison brothers to catch the ear of record company mogul Blake Chancey, who signed the brothers to his newly formed label Lucky Dog Records, a subdivision of Sony Nashville. Chancey, who had a hand in launching the careers of the Chicks, talked Sony into backing the brothers, and out came three discs: Charlie’s Life of the Party and two from Bruce, a re-released version of Wrapped, and an all-new studio disc, Long Way Home from Anywhere.

Thanks to Party’s eventual success, Charlie has since been upgraded by Chancey to Columbia, one of Sony’s priority-one country music labels. Step Right Up will be his Columbia debut; Charlie says he’s not sweating it.

“I stopped caring about what other people’s expectations are a long time ago,” he says. “I want to meet my expectations and those are continuing to make music that I am proud of, that means something to me and that will hopefully mean something to others. I don’t really care what anyone else thinks, except maybe my wife.”

*

In the middle of the Cabaret concert hall-slash-restaurant-slash-bar in downtown Bandera, a 25-year wedding anniversary party is taking place. The couple poses for pictures. Little kids chase each other around. Teens flirt. At the bar, Robison orders a drink, plops down on a stool and gazes at the scene.

“This is it. This is what you do in Bandera,” he says of the party unfolding in front of him. “You get married young and have kids and those kids have kids and you have anniversaries, birthday parties and family reunions, and you eat cake and you get drunk. But these people are stories. These are the characters in “My Hometown” or “Desperate Times” or “The Wedding Song” and those in Bruce’s “Angry All the Time” or “Just Married.'”

Bruce and his wife Kelly Willis recently celebrated the arrival of their first child, a boy they named Daryl Otis Robison. In other words, Willis and Bruce have moved one step closer to becoming the characters that populate the Robison brothers’ songs. “Yeah, it’s definitely weird calling them and hearing a kid crying in the background,” Charlie says. “Takes some getting used to, your brother being a father. But I tell you what, I’ve never been so proud of him in all of my life.”

When the subject of when he and Emily are going to start picking out carriages comes up, Robison lights up. “We talk about it all the time,” he says. “But I’ve got a record coming out and I’ll be on the road a lot. When the time’s right, we’ll know.”

There’s a reason Robison has a special attachment to the Cabaret – it’s the site of he and Bruce’s first gig. In a week or two, to celebrate the arrival of Step Right Up, Robison will headline it. More than two decades after Robison left college, left town and left his life in Bandera to pursue music, he has come full circle, playing the same stage he played before he was old enough to vote, perhaps to a lot of the same people.

“Bruce and I have always had parallel lives,” he says. “We always knew we wanted to go away and do something different. It’s ironic that I’ve wound up back here. Just goes to prove you can never really leave a place like this.”