I came up with the idea to do a story about student reporters after hearing about an incident at Plano High in which the school newspaper was censored. Not just a few words but entire stories were killed at the last second, causing the paper to run with blank pages. I didn’t work on my high school newspaper, so reporting this story was an eye-opening experience for me. From 2002.

TEXT:

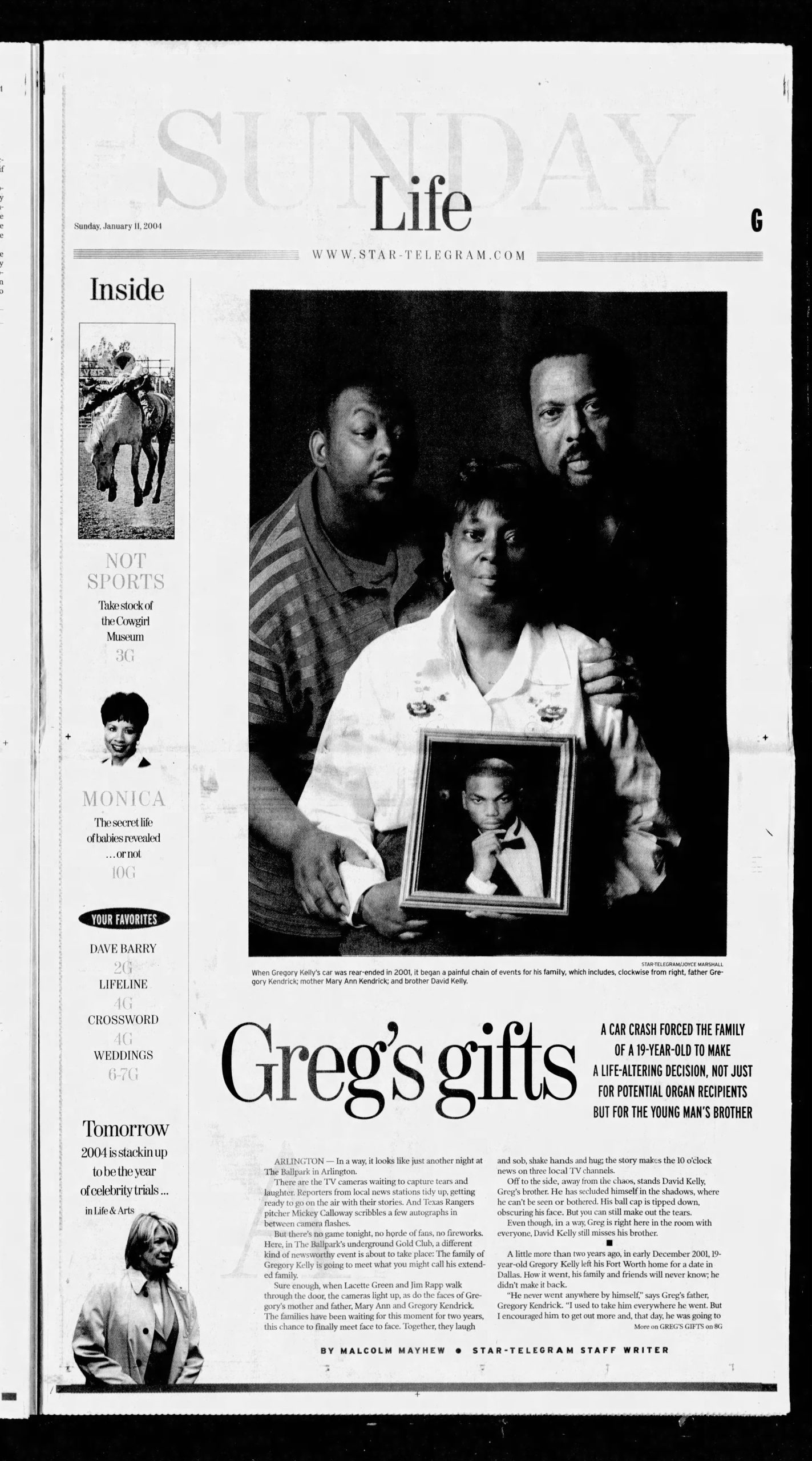

ARLINGTON – The first story idea out of reporter Michelle Wigianto’s mouth takes Tricia Regalado a little off guard.

“I want to do a story on students who want to form a gay and straight alliance group,” says 16-year-old Wigianto, the news editor for The Warrior Post, the school paper at Martin High School in Arlington.

Regalado, the paper’s adviser, lets out a sigh: “Boy, this scares me.”

Regalado is about to be further frightened: During this recent brainstorming meeting with her journalism class of about 20 students, Regalado will hear other eyebrow-raising ideas, including a piece on Enron and its effect on Martin students and an article about students with Down syndrome.

This scene has become typical in local and national high school newspaper classes. Following in the footsteps of professional journalists, high school reporters are tackling controversial subject matter, in effect stirring controversy themselves.

Last year, The Register of Omaha Central High School in Omaha, Neb., made headlines of its own when it ran a story about a football player who was allowed to participate in games even though he faced assault charges – a violation of the school district’s eligibility rules.

At Hinsdale Central High School near Chicago, the school’s principal had editions of its paper, Devil’s Advocate, confiscated after student reporters penned stories about school violence. Students reacted by posting the stories on a Web site and reporting the incident to local media.

Closer to home, high school journalism classes throughout the North Texas area are putting out papers stuffed with stories that cover weighty issues. And they are being rewarded: Both the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and The Dallas Morning News sponsor journalism competitions in which student papers and reporters are honored for, among other journalistic achievements, covering hard news. Several other regional and national journalism competitions reward students for chasing tough stories or diving into delicate subject matter.

Here’s the rub: Student reporters working on articles about how school funds are being spent, campus crime and other controversial topics quite naturally make school administrators nervous. Stories that touch on sensitive matters can put the school in a negative light, the last thing school faculties and administrations want.

This is where journalism students, advisers, principals and administrators clash and compromise: Students who want to cover school-related hard news and controversial topics are often allowed to – but with restrictions.

“The difficulty boils down to conflicting loyalties that school administrators have,” says Mark Goodman, an attorney and executive director of Student Press Law Center in Arlington, Va., a nonprofit organization that provides free legal assistance to student journalists and collects information about student free-press issues.

“Committed educators are preparing students for a democratic society, but running what is the equivalent of a business. They are very concerned about negative publicity,” he says. “The practice of good journalism involves publishing both bad and good, and once students try to cover that reality, school officials want to prevent that from happening. The result is conflict, controversy and outright censorship.”

Goodman says his organization, which has been in existence since 1974, saw a dramatic increase in legal-aid assistance calls between 1999 and 2000.

“In 1999, we received 591 calls for assistance. In 2000, it increased to 859,” he says. “That has to do with the quality of student newspapers growing, but also because more school officials are increasingly inclined to censor.”

Tricia Regalado says The Warrior Post has never been censored by the administration, at least during her time there. But she says she’s still apprehensive about running stories that could reflect poorly on the school.

“Doing [hard news] stories does scare me,” she says. “It’s not as if anyone at the school has ever said, ‘Don’t do this,’ but there’s also an understanding that you don’t want to air Martin’s dirty laundry. You think about, ‘Is this gonna be one of those stories that makes Martin look bad?’ We have to answer to the school, but it’s not just administration; it’s the other kids and other teachers. The school wants a pro-Martin newspaper.”

That hasn’t stopped The Warrior Post, which won third place in the Star-Telegram’s high school journalism competition last year for best overall newspaper, from covering news – but it has put limitations on it.

“I encourage them to pursue stories that may be hard-hitting, but they also have to understand the parameters we work under,” Regalado says. “We have a very conservative community, southwest Arlington, and people outside of the school read the paper and comment on it, and it reflects on us as a school. It’s hard for the kids to understand. They say, ‘Oh, we have First Amendment rights.’ But it’s not the same as what they learned in government. We can’t write whatever we want.”

Martin High School Principal Laura Jones agrees: Students can’t write whatever they want. In 1998, the paper outraged some in the school and the community with its end-of-the-year issue, which contained senior columns that made references to student alcohol use, and included statements asking local ministers to “leave us alone.” The Rev. Barry Cameron said, at the time, that the comments were references to complaints he and another minister had made about a Warrior Post article on counseling for teens with homosexual feelings. The paper’s then-adviser, Robbie Griffin, was placed on administrative leave and soon left the school; Jones says she will do whatever it takes to ensure that doesn’t happen again.

But Jones says she doesn’t have a problem with students running in-depth news stories, as long as they are balanced and thoroughly researched.

“I wouldn’t sit here and say, ‘No, we’re not going to do that story,’ but I would want to make sure guidance has been given by the instructor and senior staff writers, and that balance has been brought to the story,” she says.

Charlene Robertson, director of public information for the Arlington school district, says the administration will stand by the papers at its five high schools, as long as they publish within certain guidelines.

“We can support student publications when they abide by high journalistic standards,” she says. “We do find it difficult to defend them when they do cross that line, whether it’s in poor taste or when they violate ethical or journalistic standards, or when the material that they publish does not support the school. That’s where we have trouble.”

n

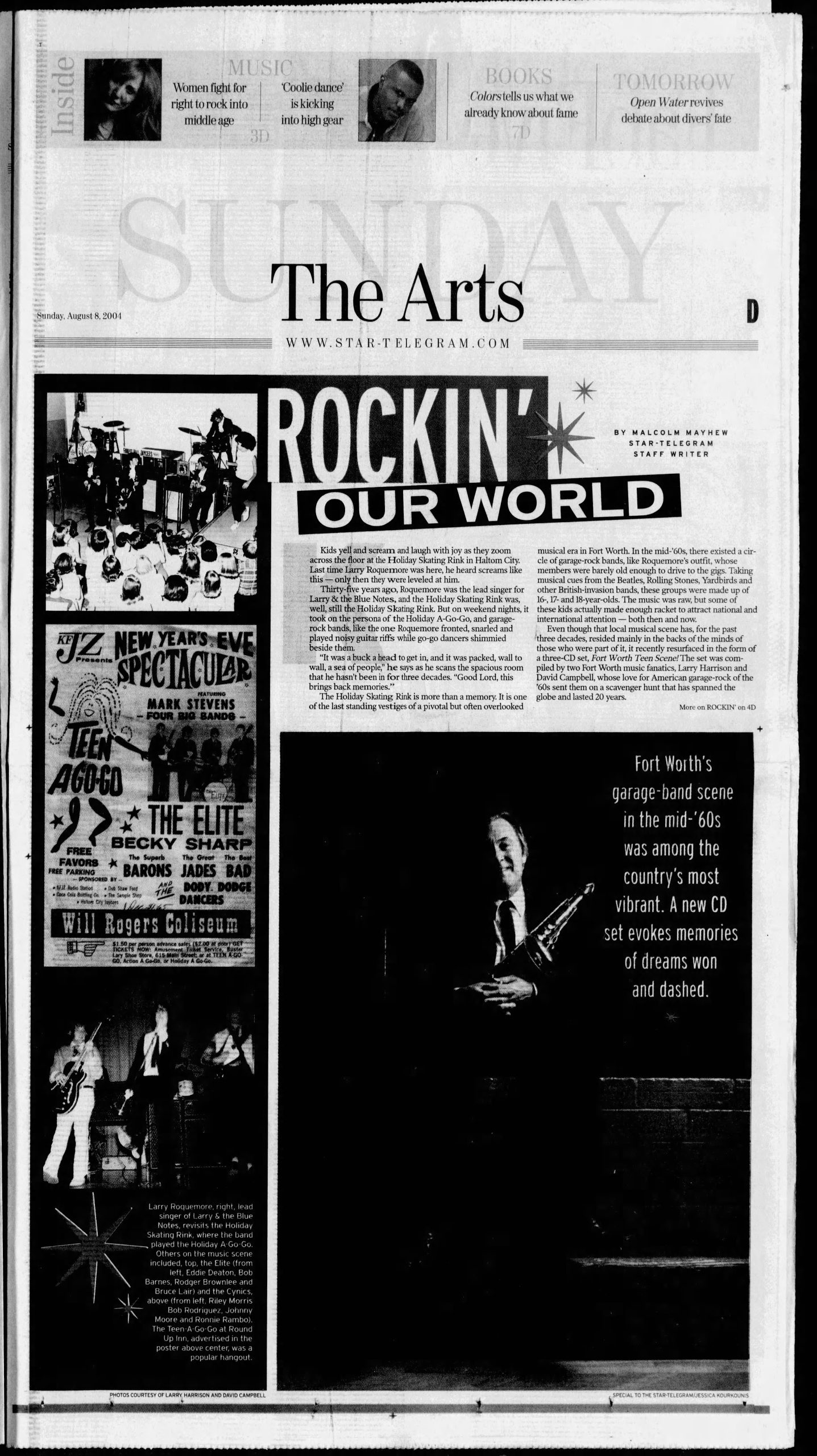

At Plano High School recently, there was some trouble.

In early February, the students in Gayle Johnson’s journalism class were finishing up the latest edition of the school’s paper, Wildcat Tales, when Johnson submitted final proofs to Principal Doyle Dean.

Johnson knew this would be a controversial issue. That’s why she submitted it to him. The paper’s center spread was about sex. The issue contained stories about safe sex, sexually transmitted diseases and the morning-after pill. There was a cartoon of a pregnant woman and a clip-art image of a condom. A student-written headline that made reference to the “horizontal tango” hung above one of the pieces.

When the paper came back from Dean, according to student and Wildcat Tales editor in chief Nick Pavlov, “it had a bunch of red X’s all over it.”

The stories with red X’s on them were cut from the paper. Since the changes were made at the last minute, Pavlov says, there wasn’t time to produce substitute stories. Where once there was copy, there was now blank space – a lot of blank space.

According to a complaint Pavlov filed with the Student Press Law Center, a story describing the process for safe sex, how to obtain protection devices and student opinions that supported abstinence was cut. A chart on STDs, their symptoms and how to get them treated was dropped. The cartoon of the pregnant woman was cut, and so was the “horizontal tango” headline.

Pavlov says he wasted little time in filing the complaint with the Student Press Law Center; he says he has also penned a letter to the school district’s superintendent.

“My concern is that this censorship was unjustified,” Pavlov says. “That headline, ‘Playing it safe when dancing the horizontal tango,’ could have been changed. The stories were of quality in content, in my opinion.”

In Dean’s, they were not.

“I can’t think of any topic we can’t address in the paper, but these stories were just not well done,” says Dean, who has been principal at Plano High School for 15 years. “I’ve not told them they can’t write about this topic, but if they’re gonna write about it, they’re gonna have to do quality articles.

“The community sees the newspaper and it’s going to have to keep with community standards. The stories have to be in good taste and well-written,” Dean says.

Danny Modisette, deputy superintendent for the Plano school district, says Dean’s actions were warranted under the school board’s policy, the district’s local version of a policy drawn up by the Texas Association of School Boards.

“I feel like he acted appropriately and within the school board’s policy,” he says. “And he acted within the scope of his position as principal.”

Plano High’s scenario raises an important issue that school administrators encounter when principals veto stories: Are they breaking the law?

“Unfortunately, it’s a complicated question,” says Goodman from the Student Press Law Center. “It is certainly possible that the principal might have violated the students’ rights, depending on a couple of things: whether the publication was, by school policy or practice, a forum for student expression where students had been given the authority to make their own content decisions.

“And whether the school principal could show that, one, the censorship was necessary to avoid a material and substantial disruption of school activities, or two, he had a reasonable educational justification for his censorship and that his censorship was not intended to silence a viewpoint with which he disagreed or found controversial or unpopular,” Goodman says.

Dean says that even though he believes he is shielded by shool board policy, he’s hoping he won’t have to mention it again.

“There have been times when the students have brought me something from the paper and I’d change a word or delete a sentence, or something like that, but I can’t recall eliminating an entire article like this,” he says. “I sat down with the students and explained to them why I did this and what our expectations are for the paper. I still have confidence in these students, many of whom want to pursue a career in journalism. I look at this as a learning experience for them, and I hope they’re looking at that way, too.”

n

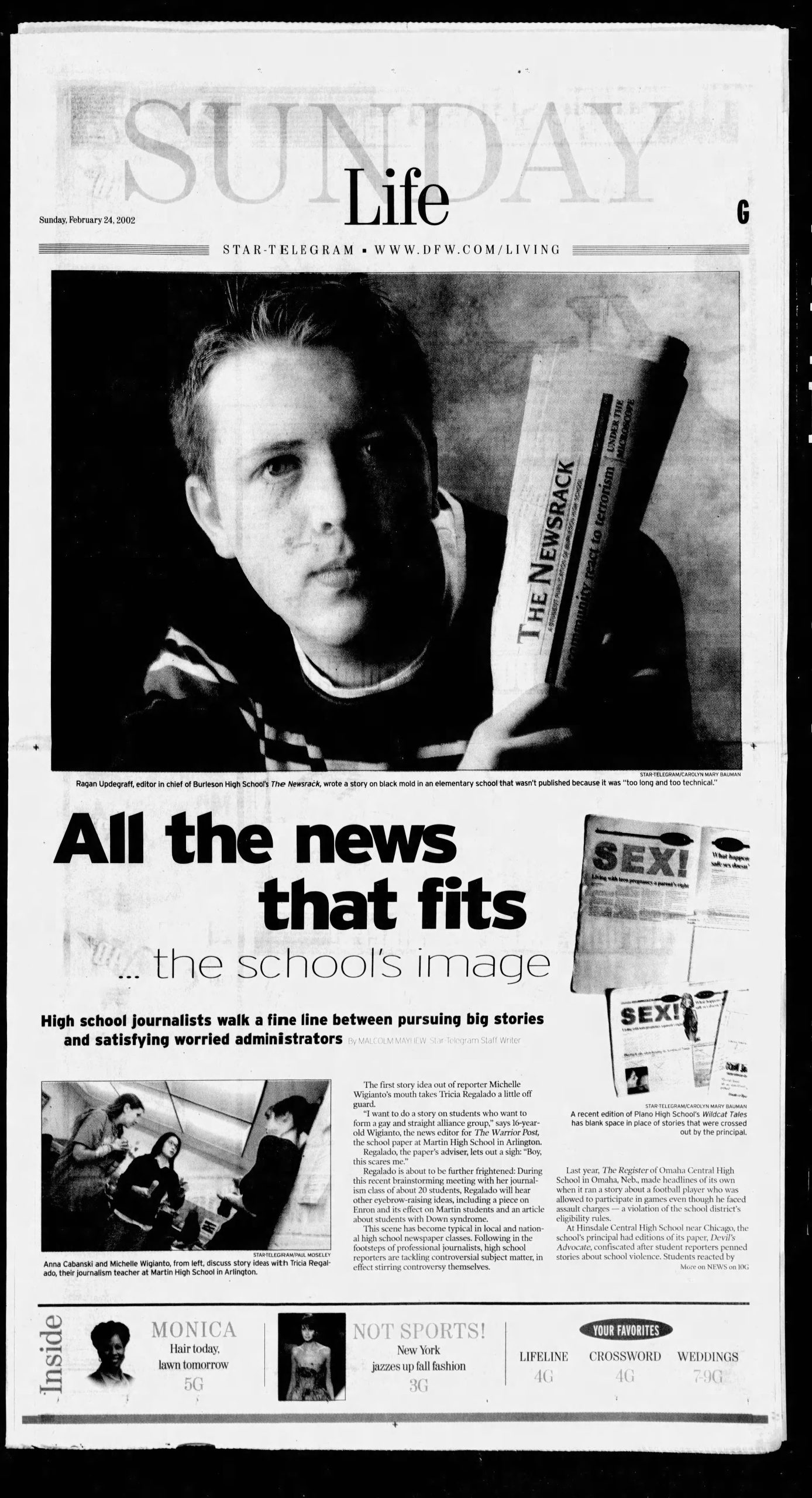

Second drafts are due today in Barbara Tatum’s journalism class at Burleson High School. The school’s monthly paper, The Newsrack, publishes in three days; it’s a bit chaotic.

The scene could be out of any newspaper newsroom: Reporters pound away on computers. Designers click their mouses, tinkering with page layouts. The reporters sometimes refer to each other by their last names – a newsroom tradition.

In the back of the room, away from the noisy mayhem, Tatum discusses a story on a school burglary with the writer of the piece, 16-year-old news editor Jack Deering, a sophomore.

Hovering above it all is Ragan Updegraff, the paper’s editor in chief. The 18-year-old senior makes his way from student to student, checking on their progress as deadline looms.

Updegraff is considered the paper’s strongest reporter and writer: In 2001, he won first place in the state for a UIL feature-writing contest, and this and last year, he penned provocative stories about the school’s random drug-testing policies for athletes and the athletic department’s proposal to spend $560,000 to $720,000 to re-turf its football field with a synthetic turf.

He and Deering also uncovered a story that, according to Updegraff, has yet to run in its entirety: Black mold was found last year at Mound Elementary School, a school in the Burleson school district.

“A teacher found black mold there on Nov. 6,” Updegraff says. “Jack did the first story on it, just the fact that it was found and it was removed from the building. But that was just one spot. There were students and teachers elsewhere in the building getting sick, and their symptoms coincided with those who become exposed to toxic mold. Students were having nosebleeds and some developed chronic asthma.

“I talked to a lot of people – the school nurse, a professor at Texas Tech who gave me some good info as far as it being linked to health problems, some teachers there,” Updegraff says. “I worked on it pretty intensely for about two weeks.”

The follow-up piece never ran, though.

“I guess it got a little more complicated than what you might expect to see in a high school newspaper,” Updegraff says. “I was told it was too complex and it didn’t go with what readers are interested in. Our football team had just made the playoffs, and that was important, and that took a lot of our space. I was pretty hacked.”

Tatum, who has taught journalism at Burleson High School for 25 years, says the piece didn’t run because “it was too long and too technical.”

“It was really well written, but it wasn’t written so our audience could understand it,” she says. “And there wasn’t a strong enough tie-in to our readers. I expected to see some kind of tie-in at school, like talking to some of the kids whose younger siblings go to Mound. All of his research was wonderful, but in the end, there wasn’t anything to tie it to our students.”

The story is on hold; Tatum says it may run, if changes are made to it.

The mold is in the process of being removed from the school, says Mound Elementary School Principal Pam Ehrich. “The central administration responded rapidly and thoroughly,” she says. “Parent meetings were held. Letters were sent home. And some of the students were relocated to other schools.”

Though Updegraff’s piece has yet to run, this is the type of hard-hitting news he says he is committed to doing. And Tatum says that she and school Principal Richard Crummel

have given Updegraff and the rest of the paper’s staff plenty of room to do that.

“Our principal is a great guy. He doesn’t interfere with what we do,” Tatum says. “But we also have a good working relationship with him. If we’re doing something controversial, I let him know.”

Crummel, who has been Burleson High’s principal for seven years, says that’s the main reason why he is supportive of Tatum and her class, and lets them have free journalistic reign: They communicate with him.

“She keeps me informed,” he says. “That’s the key, informing me of what they anticipate doing. There’s not a subject that I’ve ever said ‘absolutely not’ to. In the course of Barbara and I talking about story ideas, I’ve said, ‘I don’t want to go there,’ but those were stories about individual students, like teen pregnancy or something else like that. My suggestion usually is, ‘Let’s talk to students in general, not just single out one.’ “

Updegraff says his poking around the campus in search of stories has frazzled some of the faculty and staff. But that, he says, is what he is supposed to be doing.

“I know I’ve made some people nervous, but as a journalist, I want to push the envelope a bit,” Updegraff says. “I made it a point to do well-researched stories, and that sometimes means putting people on edge.”

Tatum says Updegraff hit a roadblock within the school when he was writing the drug-testing story, a piece that questioned the school’s random drug-testing policies of football players and other athletes. Last school year, Tatum says, the majority of the testing wasn’t done until after football season had ended, prompting the paper to find out why.

“We asked one of the school’s athletic trainers for the records and results of the tests, and we were told that information was not available,” Tatum says. “So Ragan took the initiative to call Huguley Hospital, where the records were, and they just handed over everything.

“It was a really balanced story,” Tatum says. “You’re just trying to lay the facts out. You don’t ever go into a story trying to crucify somebody. Turns out, the testing was being done right, for the most part. Richard was fine with us doing this. He just said, ‘Make sure you follow it up.’ And we did. We’re a lot happier with the way the drug-testing is being done now.”

That the athletic department tweaked its policy as a result of one of his stories is, for Updegraff, a nice slice of satisfaction.

“Even though we are a dinky high school paper,” he says, “it is nice to know that we make an impact.”

n

Michelle Wigianto’s Gay-Straight Alliance story will not run – not because of its subject matter, says The Warrior Post’s editor in chief, Erika Barrera, but because, in her opinion, it’s not yet a story.

“The club hasn’t been formed yet,” says 17-year-old Barrera, a Martin High senior. “Lots of students want to form clubs. When that club is formed, we’ll do a story on it.”

The Star-Telegram did consider it a news story and ran a Page One article about the controversy over the proposed club on Jan. 6 in its Arlington edition.

But running a paper, any paper, involves many judgment calls, and different editors will arrive at different decisions. And certainly student journalists will continue to feel pressure to tread carefully with controversial subject matter. In general, however, a more aggressive attitude has been adopted by journalism advisers and students, and condoned by principals, throughout many North Texas high schools.

“Our paper has addressed sex, drug use, domestic violence, every kind of topic you can think of, at one point or another,” says Chuck Boyd, principal at Arlington Heights High School in Fort Worth. “I’ve got a real good relationship with the newspaper staff and the journalism teacher. In the three years I’ve been here, I haven’t had a run-in with a student or teacher over a story.

“But there will come a day, I’m sure.”

Why the law is mightier than the pen

High school principals and administrators have a surprising amount of power when it comes to policing the content of school newspapers and other student publications.

Principals have the right to, in a roundabout way, censor stories. This is outlined in a policy written by the Texas Association of School Boards and based on a 1988 Supreme Court ruling that upheld the right of high school administrators at Hazelwood East High School in St. Louis to censor student-penned stories about divorce and teen pregnancy.

“The Hazelwood case did not allow censorship of the paper but it did allow prior review from administration,” says Charlene Robertson, director of public information for the Arlington school district. “It did overrule a campus’s right to arbitrarily censor a school’s paper, but it also outlines specific guidelines that the school’s publication must meet.”

Robertson says local school boards may make their local policies “more strict but not less” than the state association’s policy.

The first line of Plano’s policy says, “All publications edited, printed, or distributed in the name of or within the District schools shall be under the control of the school administration and the Board.”

The Fort Worth school district draws its student-publication guidelines under a similar policy.

“The principal does have a right to review the article and determine whether it does or does not need to be in the paper,” says Sue Guthrie, assistant superintendent for secondary-school management for FWISD. “We do follow federal law and encourage our teachers to review the articles before they’re published. But I think [the story] would have to be nonfactual, or slanderous, or something that would hurt another person’s job or relationship with the school, for us to pull it.”

Malcolm Mayhew, (817) 390-7713 mmayhew@star-telegram.com

PHOTO(S): Paul Moseley;Rodger Mallison;Carolyn Mary Bauman