Originally published March 20, 2005

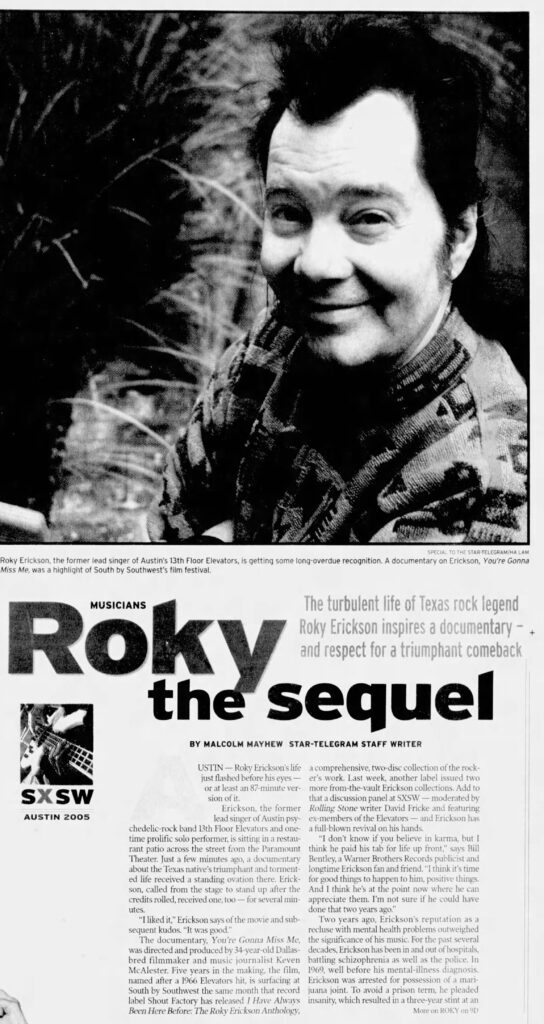

AUSTIN – Roky Erickson’s life just flashed before his eyes — or at least an 87-minute version of it.

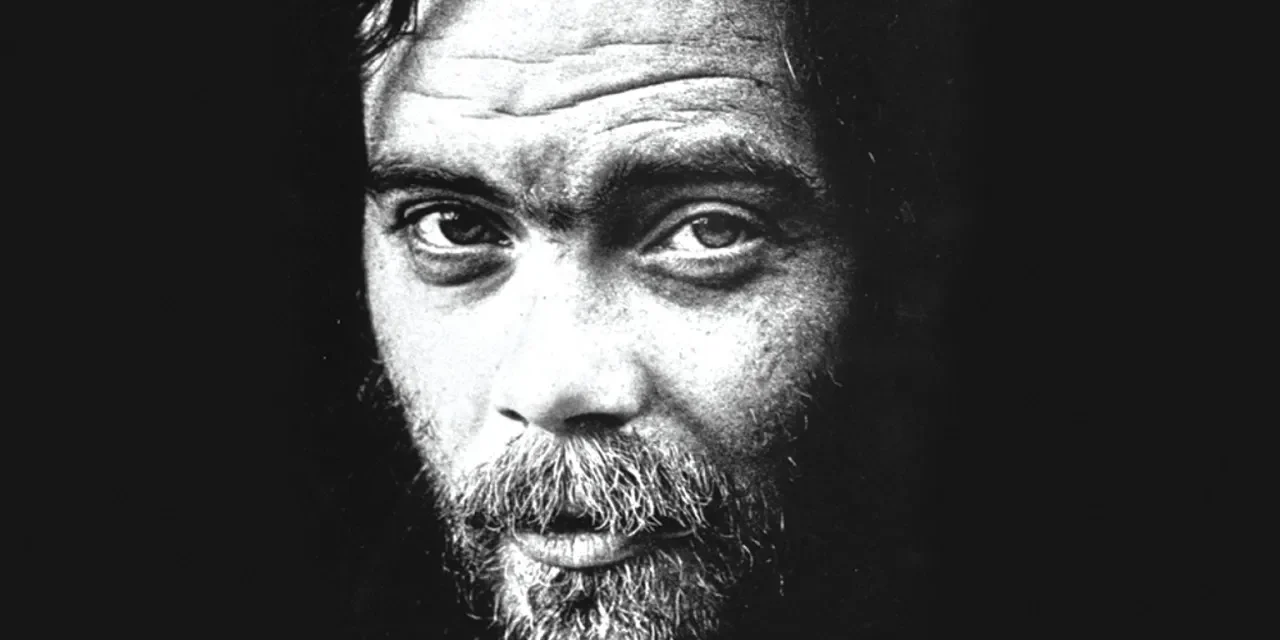

Erickson, the former lead singer of Austin psychedelic-rock band 13th Floor Elevators and one-time prolific solo performer, is sitting in a restaurant patio across the street from the Paramount Theater. Just a few minutes ago, a documentary about the Texas native’s triumphant and tormented life received a standing ovation there. Erickson, called from the stage to stand up after the credits rolled, received one, too — for several minutes.

“I liked it,” Erickson says of the movie and subsequent kudos. “It was good.”

The documentary, You’re Gonna Miss Me, was directed and produced by 34-year-old Dallas-bred filmmaker and music journalist Keven McAlester. Five years in the making, the film, named after a 1966 Elevators hit, is surfacing at South by Southwest the same month that record label Shout Factory has released I Have Always Been Here Before: The Roky Erickson Anthology, a comprehensive, two-disc collection of the rocker’s work. Last week, another label issued two more from-the-vault Erickson collections. Add to that a discussion panel at SXSW — moderated by Rolling Stone writer David Fricke and featuring ex-members of the Elevators — and Erickson has a full-blown revival on his hands.

“I don’t know if you believe in karma, but I think he paid his tab for life up front,” says Bill Bentley, a Warner Brothers Records publicist and longtime Erickson fan and friend. “I think it’s time for good things to happen to him, positive things. And I think he’s at the point now where he can appreciate them. I’m not sure if he could have done that two years ago.”

Two years ago, Erickson’s reputation as a recluse with mental health problems outweighed the significance of his music. For the past several decades, Erickson has been in and out of hospitals, battling schizophrenia as well as the police. In 1969, well before his mental-illness diagnosis, Erickson was arrested for possession of a marijuana joint. To avoid a prison term, he pleaded insanity, which resulted in a three-year stint at an institution in Rusk, Texas, and electroshock therapy. Years later, Erickson had another run-in with the law, when he was arrested on charges of mail fraud.

McAlester’s movie chronicles those tangles with the police; Erickson’s time in Rusk (which some believe triggered his schizophrenia); his crumbling relationship with his mom; the drugs he took and the price he paid; and his subsequent recovery.

Erickson’s condition has been part of his myth — that of a groundbreaking talent driven to seclusion and irreparably damaged by a torturous mental health problem.

“I’d always wondered why no one had made a documentary about him. It’s such a fascinating and tragic story,” says McAlester. “There have been concert [films], but never one that told the story of his life.”

Combining old concert footage and homemade movies with current interviews of the 57-year-old Erickson, his brother Sumner; their mother, Evelyn; and various musicians whose lives and music were influenced by Erickson, McAlester pulled off a difficult juggling act: telling both sides of Erickson’s story — his music, his health.

“When we first started shooting it, the movie was just going to be about his career,” McAlester says. “As we got into it, it became clear that there was also this story of family drama. There was a lot of confusion as to which one was more important. I think you could take any year of his life and make a movie out of it. I think you could make a movie out of him talking for two hours. But the struggle for us, while editing this movie, was how to combine the two aspects of his life in a way that worked. Did we achieve that goal? That’s for you to decide.”

“I think it’s very, very well done,” says 42-year-old Sumner, who is Roky’s legal guardian. “There’s no way to get around the negative things that happened to Roky. But too many people focus on that part of his life. There was another newspaper that called him the Syd Barrett of Texas. I hate that. Not enough people know how instrumental he was in developing a regional and national psychedelic-rock sound.”

Warner Brothers’ Bentley has helped change that. In 1990, he pieced together an Erickson tribute record, Where the Pyramid Meets the Eye: A Tribute to Roky Erickson, which featured several heavyweight artists — R.E.M., Fort Worthian T Bone Burnett, Primal Scream and ZZ Top — covering Erickson/13th Floor Elevators songs. “It didn’t sell a whole lot of copies, but it raised awareness of his music,” Bentley says. “That was the goal.”

Bentley also helped produce the new compilation from Shout Factory; he wrote the liner notes, too.

“I just feel a real passion for his music,” says Bentley, who grew up in Houston. “I was 15 or 16 when I got turned onto [the band] and started seeing them live. I used to see them at these small places in Austin and Houston, and when you’re seeing a band like that at such an impressionable age, it affects you. They had such a huge sound, and I think that sound played a pivotal role in the birth of psychedelic rock.”

When he thinks about those times, Erickson says, he chooses to focus on the positives that came out of them.

“I think of the good things, the excitement,” he says. “Breaking in a new theme: psychedelia. Those were the good things.”

Although Erickson never really stopped making records, his mental health made it difficult. Performances became sparse.

But everything changed for the good when, two years ago, Sumner took Roky to Pittsburgh, where he was given a different kind of medical and therapeutic treatment.

“That’s where I was living at the time,” says Sumner. “I knew of someone who wanted to meet him and work with him, get him on some better medications and therapy. And it worked very well. He is in such good health and spirits these days. For us, and for him, this is truly a glorious time.”

Erickson is in such great shape that he’s even playing SXSW. The Roky Erickson Ice Cream Social is an annual fund-raising gig, a gathering of musicians happy to help their friend pay down his medical bills. Erickson planned to perform at least one song — Starry Eyes — and maybe two.

He’s also been working on new songs.

“I wrote one called Singing Grandfather,” he says. “I might play it.”

Whether he’ll ever record a full-length album again remains to be seen.

“We’re playing everything by ear,” says his brother. “Right now, we’re just ecstatic about him being in such great condition. I know the stuff that’s happened in the past won’t ever go away. But hopefully it’ll fade into the background and people will just focus on the genius of his music.”