Originally published June 18, 2000

DALLAS – Jane Broadway’s office seems innocuous enough – papers are scattered about her desk, a laptop softly chirps, the phone occasionally rings. Like a doctor’s waiting room, the walls are dotted with framed photos and awards attesting to some of her professional accomplishments.

But it isn’t until you really look at the photos that you fully grasp what Broadway does for a living.

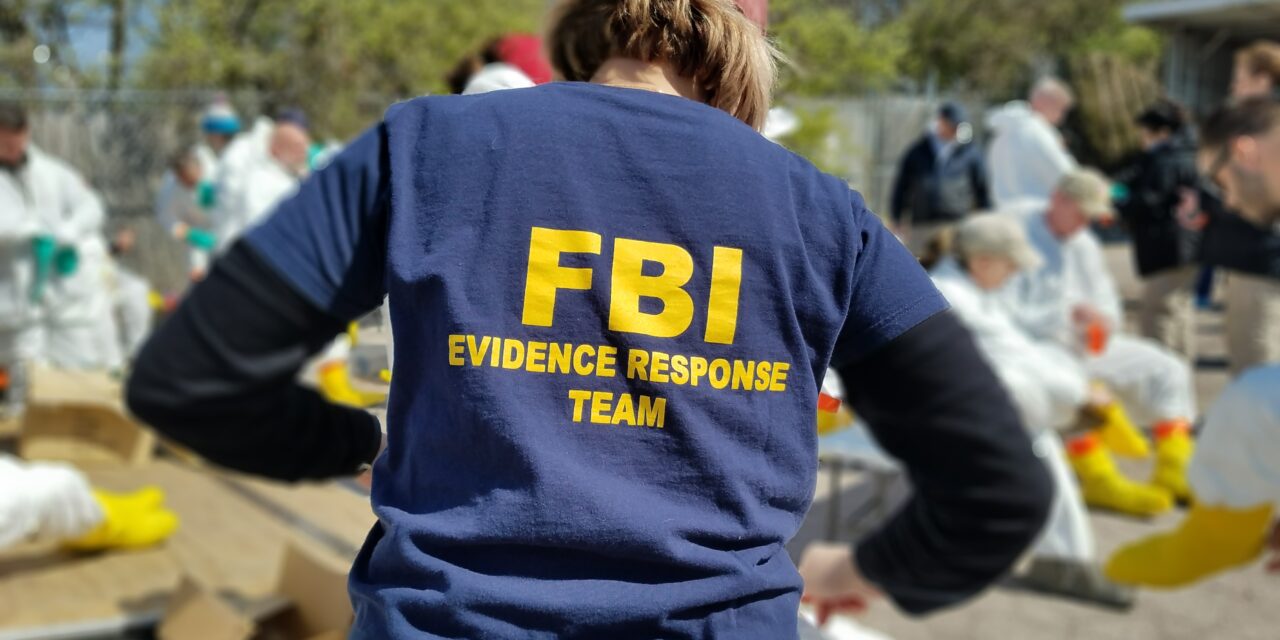

One particular snapshot says it all: Looking like a victorious company softball team, Broadway and the rest of her male and female colleagues are smiling for the camera, some of them resting on their haunches, others standing. But behind them isn’t a ball field – it’s a horror story: the twisted, smoldering remains of the U.S. Embassy in Dar Es Salaam in Tanzania, Africa, which a bomb tore through in August of 1998, killing 11 people and injuring 86.

Broadway leads the Evidence Response Team, or ERT, for the FBI in Dallas. And according to the bureau, she and her team are very good at their job, so much so that her division of the ERT is the most widely used such team in the FBI. Throughout the past few years, they’ve been summoned to some of the most notorious tragedies in the world: the embassy bombings in Africa, the Branch Davidian standoff in Waco, the Oklahoma City bombing, the mass burials on ranches near Juarez, Mexico.

Closer to home, the team has helped with the Opal Jennings kidnapping case, the massacre at Wedgwood Baptist Church and the beating death of 18-year-old Kyle McElroy in Troup.

But despite having the respect of her fellow agents, despite the awards and accolades from the bureau, despite years of facing death and tragedy every day, Broadway says it never becomes easy to deal with.

“You never get used to it,” she says, staring at the U.S. Embassy bombing photo. “You separate yourself from it. You have no choice but to. But do you ever get used to it? No.”

***

The Dallas FBI building where Jane Broadway works is not what you’d expect, especially if your idea of the FBI has been formed by The X-Files. Tucked inside the city’s West End area, the space is carved out of upscale red and white brick and shares a roof with the corporate offices of a popular restaurant chain.

Inside, you will not find men in black sunglasses smoking cigarettes, whispering among themselves or talking into their jackets. The only immediate signs that this is not your typical corporate atmosphere: a metal detector. That is, until you get upstairs.

There, it’s maximum security: Plates of bulletproof glass separate a waiting room from a receptionist area, wallet-size cards are electronically used to trigger doors and elevators, visitors must don stick-on badges and be escorted by an agent at all times.

The waiting room leads to mazes of offices where FBI agents buzz about, some dressed in suits, some in casual khakis. Everyone is friendly, offering a “hi,” or small talk. Unlike Hollywood’s version of the FBI, no one here swaggers.

It is here that Broadway spends most of her time. And she’s the first to admit it’s not always very exciting.

“I spend half my time doing paperwork,” says Broadway, a soft-spoken, slender woman with short brown hair pushed to the side. “Ordering, restocking supplies, making sure we have everything we need in case of a call-out. It’s really kinda boring sometimes.”

But if real FBI work can be much more mundane than what you see on TV, it can also be much more dramatic and horrifying – and emotionally demanding. Although much of her day-to-day work involves “boring” office work, she knows a phone call can spice up her life at any time. Special Agent Broadway’s official job title is ERT team leader and overall response coordinator. She’s in charge of a 32-member team that is called upon when local law enforcement needs special expertise with a crime scene or when a massive crisis occurs, such as a bombing or kidnapping, and an extensive amount of lab work and legwork is needed.

In seconds, she and her team can be ready to respond to any crime-related event. A trailer equipped with thousands of dollars’ worth of high-tech, evidence-gathering equipment – like the one featured in the Kevin Costner/Clint Eastwood movie A Perfect World – sits only a few miles away, in a modest warehouse; each member carries in his or her car a bag of bare-necessity supplies: a change of clothes, toiletries. And, like other special agents, they all carry guns.

“We’ll go in a minute’s notice, national, local, international, wherever,” says Brent Chambers, one of four team leaders. “We’re one of the only teams in the bureau that is equipped to go anywhere in the world in a minute’s notice.”

One unique characteristic of the ERT is that, with the exception of Broadway, who’s the full-time team leader, all the members of the group have assignments outside the team and have volunteered to be part of the elite outfit. Each has his/her own other FBI job: public corruption, hazardous material, violent crimes and so on.

“We’re like a volunteer fire department,” says Broadway.

Each member brings to the team a wealth of specialized knowledge. Broadway, for instance, is a former Army medic. Special Agent Katy Gossman is a former helicopter pilot. Deborah Eckart, who works out of the FBI’s Fort Worth office, is a one-time nurse. Two other team members, Chambers and Special Agent Michael Hillman, were police officers before they joined the FBI.

“It’s a well-trained cadre of professionals and experts; that’s why they get used so often,” says Assistant Special Agent In Charge Bob Garrity, who is responsible for the day-to-day operations of the entire Dallas FBI division, the 10th-largest field office in the bureau. “Much of what they do is crime-scene work. It’s tedious, methodical, painstakingly organized. And it can also be traumatic. Very traumatic.”

***

FBI Special Agents and Evidence Response Team members Jim Kendall and Deborah Eckart are trying to put the unspeakable into words.

Sitting at Broadway’s desk while she’s running an errand, they bring up the Opal Jennings case, in which the ERT was dispatched last March to search for the missing 6-year-old Saginaw kindergartner for several days.

Their work helped lead to the arrest of Richard Franks, whose trial is scheduled to start June 26. The 30-year-old is being charged with aggravated kidnapping in Opal’s disappearance. Following his arrest in August, Franks told authorities he gave the girl a ride to a convenience store and dropped her off.

According to his arrest warrant affidavit, Franks said the child made sexual advances toward him. Experts say sex offenders often believe their victims approach them sexually. The little girl has yet to be found.

The conversation shifts to Kyle McElroy. The 18-year-old man was found beaten to death in New Summerfield, a small town 10 miles south of Troup in East Texas. The ERT worked the crime scene where McElroy’s body was found; they couldn’t move his body until all the evidence-gathering was done.

The Cherokee County Sheriff’s Department and the FBI have arrested three men in the kidnap-slaying: Daniel Rios, 26; Ernesto Bailon, 17; and Alfredo Romero, 23. All three face capital murder charges. A woman who made ransom calls to McElroy’s family is still on the run, the FBI says.

Oklahoma City was another trying situation, Eckart says. The April 19, 1995, bombing, which killed 168 people, found the ERT spending two weeks at the site, where, initially, they helped look for survivors, then sifted through the building’s remains for evidence.

One team was set up at the local morgue, where ERT members examined bodies for bomb shrapnel and other clues.

“Being around death, all the smells, the sounds, the sights, the families and friends crying, it’s difficult. You never forget it, especially when kids are involved,” says Kendall, 43, who has two children of his own. “But we work as a team, and we’re all very supportive. You just try to take care of each other.”

Sometimes, the scents and sounds of death are so emotionally overwhelming, ERT members seek counseling – among themselves, with religious counselors, with the FBI itself.

McElroy’s case was especially difficult for some team members.

“After Troup, we had a crisis debriefing in which everyone was required to go,” says Garrity. “Chaplains sat and talked with the group about trauma and how it may be affecting them. We had agents who were having a difficult time sleeping at night. They kept thinking back to the scene.

“This particular case was traumatic in two senses: One, we had a very high-intense investigation looking for a victim who we believed was still alive; two, we then discovered he was dead,” Garrity continues. “When we learned he was dead, there’s that unknown equation: “Would he be alive if we hadn’t made a mistake?’ ‘Could we have prevented his execution?’ We later learned that he was already dead before the first phone call had been received by the father. But racing against the clock and the unknown, then, of course, to discover his body beaten beyond recognition, that can be extremely stressful.”

But even that case might not be the most nightmarish they’ve faced. Out of the dozen or so high-profile crime scenes the Dallas ERT has been called to investigate, the massive burial near Juarez, Mexico, say the agents, remains truly unforgettable.

“It was the first joint investigation of that kind between us and Mexico,” Broadway says. “But it wasn’t safe for us to be there.”

In November of last year, 65 FBI agents and 600 Mexican military and federal judicial police descended upon three ranches in different parts of Ciudad Juarez, across the border from El Paso. A U.S. government informant tipped off authorities, saying there might be as many at 100 bodies buried there. The drug cartel of the Carrillo Fuentes family controls the area.

Of those 65 agents, eight belonged to the Dallas ERT. Fearing the ERT members were targets, the Mexican government gave them bodyguards, which, initially, added to an already tense atmosphere.

“Psychologically, this was not the best situation,” says 30-year-old Special Agent Michael Hillman, the youngest member of the ERT. “It can become difficult when you’re deployed and you’re away from your family and you don’t know when you’re going home. On top of that, we were concerned about our safety, surrounded by these bodyguards that, at that point, we really didn’t know, working long hours, on the news every night and digging up bodies.”

Then there were the sandstorms, which twice forced the ERT to halt its work.

“It felt like bullets hitting us,” says Chambers. “You could hardly see in front of you. We had to leave, they were so bad.”

Despite the fears and setbacks, the Dallas ERT, with Broadway leading the way, found a mass burial site where nine bodies were excavated, three of which were those of Americans. Chambers says it was an excruciating assignment, but not one without a payoff.

“We were definitely living minute-by-minute there,” he says. “You put your faith in God and keep going forward. We were there for the greater purpose – to recover evidence that, hopefully, will prosecute someone. I don’t want to sound John Wayne, but that’s why I got into the bureau – to make a difference.”

***

Jane Broadway also wants to make a difference – always has. And her dedication, discipline and talent have led her to the top of her profession.

Born 35 years ago in Atlanta, Broadway grew up on a 200-acre farm in Virginia. Her mother was a nurse, her father an employee of the Department of Agriculture.

Right out of high school, Broadway joined the Army Reserves, while she started college at Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Va., majoring in economics. Before she had even finished school, she applied for a CIA job, a rigorous process that results in few hires among the thousands of applicants every year.

Broadway was one of the chosen few. “I always had a taste for adventurous, off-the-beaten-path-type things,” she says. “I went to work for the CIA before I even finished school” – work she still isn’t supposed to talk about.

“All I can say is, it had to do with money.”

In 1990, Broadway applied for a position with the FBI and, in November of that year, began training at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Va.

“It’s four months of school, but you’re paid for it,” she says. “Your paychecks start the day you do. But it’s not like going to class, then going home. You live there. It’s like boot camp. Everyone gets the same block of training and skills and knowledge. You get more specialized when you get in the field and get assignments.”

Broadway’s first post-school assignment: bank fraud.

She was sent to Dallas in March 1991, to investigate a series of bank failures and savings and loan scams. “As a brand-new agent, it was very complex work,” she says. “I had to review all these complex financial land transactions, and I had never even signed my own loan documents.” Her work on the case led to indictments of several bank executives and land developers.

A year later, the Dallas branch of the FBI formed the ERT, taking cues from similar teams in Boston and Los Angeles.

One of the first to volunteer for the team, Broadway has since worked her way up to team leader and coordinator. It’s a job she relishes – even though it sometimes gives her nightmares.

“The one that still bothers me the most happened a few years ago in Pottsboro out in East Texas,” she says. “A 16-year-old boy kidnapped a little girl out of her bedroom window. He sexually abused her before he killed her. We were brought in to process the house [for evidence] where the kid was from and the storm cellar where her body was found.”

Their work proved to be imperitive to the investigation. In 1996, Jonathan Joe Johnson pleaded guilty to abducting and killing the toddler, 23-month-old Tabitha Baker. He received a life sentence for three felony counts: murder, aggravated sexual assault of a child and aggravated kidnapping. In 30 years, he will be eligible for parole.

Authorities said there was evidence showing that Johnson raped and strangled Baker.

“This case was so up-close and personal,” Broadway says. “We had to be down there in the cellar for hours at a time with [the body], meticulously working around her. It was the first time I thought, ‘How could someone do this to someone else?’ I remember them all, but that one still bothers me.”

***

The stories go on, with most ending unhappily – dead bodies, crumbled buildings, the missing still missing.

The one ray of light that shines down on such cases, Broadway says, is that she and her team often get a first-hand view into the minds of criminals, information that the ERT – and the entire FBI – can learn from.

Broadway cites two cases as examples: that of Richard Franks, the man believed to be behind last year’s disappearance of Opal Jennings, and that of Larry Ashbrook, the man who fatally shot seven people last year at Wedgwood Baptist Church, before killing himself.

“It’s really fascinating,” she says, flipping through a photo album of pictures of Ashbrook’s disheveled house. In the disturbing photos, trash is scattered everywhere; a toilet is overflowing.

“You can tell so many things about some people by their home,” Broadway says of the psychological-analysis aspect of their work. “What they did before they left, the kind of temperament they were in, the way they lived. We learn so much from this.”

Not that gleaning such useful information makes the stress and pain any easier to handle – especially when the crimes seem, as they often do, to defy explanation. The men and women who work on the ERT find satisfaction in a job well done, in seeing successful prosecutions come from their work. But the cost is great, and they all recognize it.

“The hardest thing is realizing how cruel people can be to other people,” says Special Agent Brent Chambers, 36, who has a wife and kids. “You see the dead bodies, the thoughtlessness of people and how they can be so hurtful. You never get used to it, but you learn to deal with it. Talking to other team members helps more than anything. You can’t keep it in. There’s no way.”

Malcolm Mayhew, (817) 390-7713 mmayhew@star-telegram.com

PHOTO(S): Dale Blackwell;Associated Press;FBI;Carolyn Mary Bauman