By the mid-2000’s I was getting a little burned out on music. Covering Steve Miller and Ozzfest and the Warped Tour every year at Starplex was taking a toll. My editors knew it and wanted me to shift my focus to writing slice-of-life and human interest stories. In 2004, I took on this massive project – a look at organ donation and how it affects the lives of both the recipients and the family members of the donors. Not an easy story to write but it challenged me in ways I hadn’t been challenged as a writer before.

Text:

ARLINGTON–In a way, it looks like just another night at The Ballpark in Arlington.

There are the TV cameras waiting to capture tears and laughter. Reporters from local news stations tidy up, getting ready to go on the air with their stories. And Texas Rangers pitcher Mickey Calloway scribbles a few autographs in between camera flashes.

But there’s no game tonight, no horde of fans, no fireworks. Here, in The Ballpark’s underground Gold Club, a different kind of newsworthy event is about to take place: The family of Gregory Kelly is going to meet what you might call his extended family.

Sure enough, when Lacette Green and Jim Rapp walk through the door, the cameras light up, as do the faces of Gregory’s mother and father, Mary Ann and Gregory Kendrick. The families have been waiting for this moment for two years, this chance to finally meet face to face. Together, they laugh and sob, shake hands and hug; the story makes the 10 o’clock news on three local TV channels.

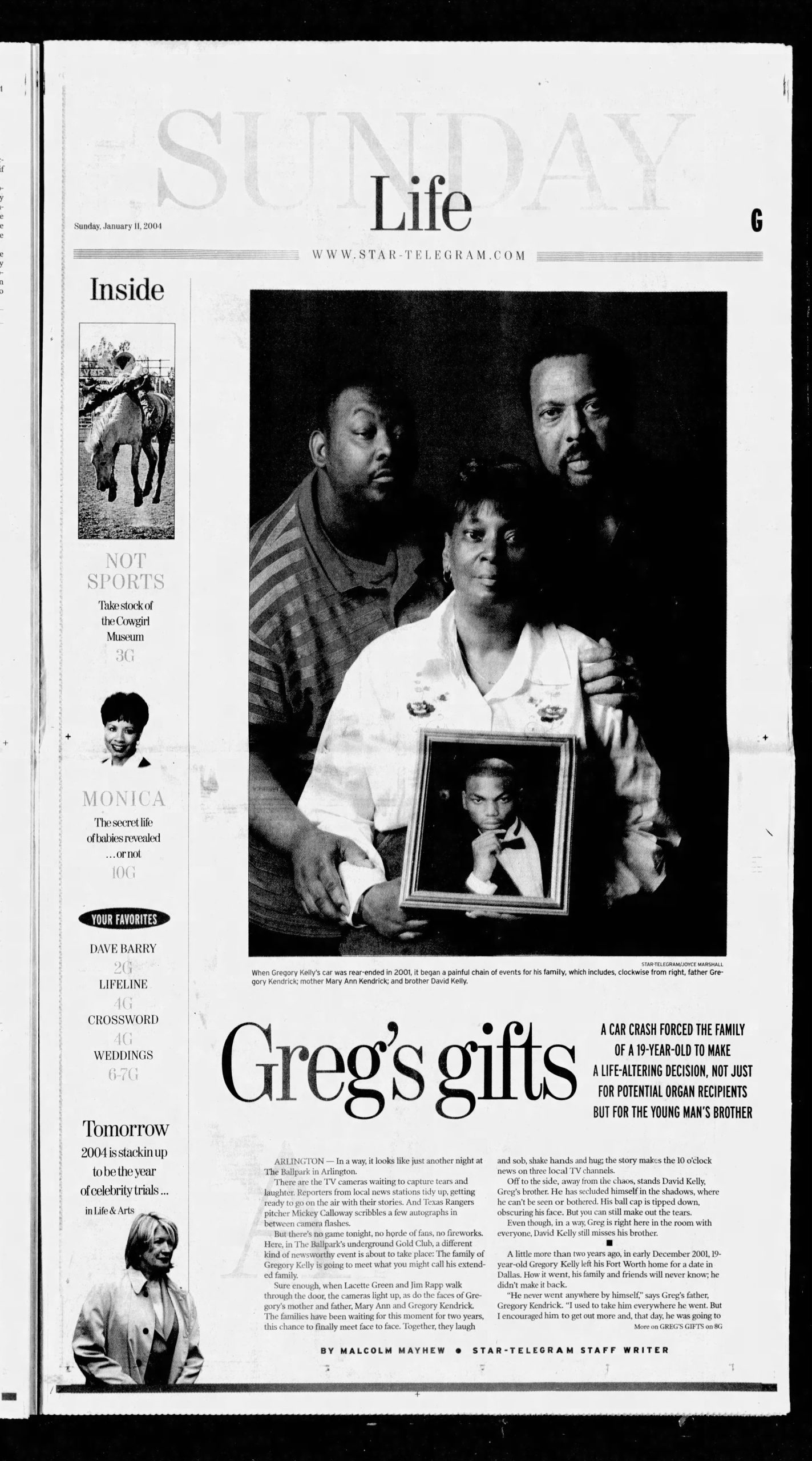

Off to the side, away from the chaos, stands David Kelly, Greg’s brother. He has secluded himself in the shadows, where he can’t be seen or bothered. His ball cap is tipped down, obscuring his face. But you can still make out the tears.

Even though, in a way, Greg is right here in the room with everyone, David Kelly still misses his brother.

*

A little more than two years ago, in early December 2001, 19-year-old Gregory Kelly left his Fort Worth home for a date in Dallas. How it went, his family and friends will never know; he didn’t make it back.

“He never went anywhere by himself,” says Greg’s father, Gregory Kendrick. “I used to take him everywhere he went. But I encouraged him to get out more and, that day, he was going to visit a friend in Dallas. I remember he called me five or six times, because he was having a hard time finding his way around. He called me and said, ‘Look Dad, I think I’m gonna come back home,’ but then he found the exit. The last call I got from him, he said, ‘Dad, I found it.’ “

Later that night, while he was traveling on Garland Road, Greg’s car was struck from behind by another vehicle. He suffered massive head injuries. On Dec. 3, at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas, where Greg had been rushed, he was pronounced brain-dead. His last few hours were spent on a ventilator.

It was then, at that moment, that representatives from the Southwest Transplant Alliance were called by hospital officials to approach the family about donating Greg’s organs, in hopes that his death could bring someone else life.

Whenever there’s a death at a U.S. hospital, or someone at a hospital is pronounced brain-dead, the local organ donation agency is automatically called by hospital officials. Southwest Transplant Alliance — one of 59 nonprofit organ-donation agencies across the country — responded to Greg’s death because he died in Dallas, which is in Southwest’s territory.

However, after being asked to wait at the hospital for representatives from Southwest to get there, Greg’s family left.

“We didn’t even have a chance to meet them. They had already left, they were so distraught,” says Pam Silvestri, Southwest’s community education director. “They were devastated, which is perfectly understandable.”

“I was really out of it,” Mary Ann Kendrick says at the family’s Fort Worth home. “I was hoping what had happened was just a bad dream. You know it’s not, but it’s what you’re hoping.”

But Laura Rodriguez, a Southwest representative, persisted. By phone, she reached Mary Ann at home, talking to her for more than an hour, going over the nuances of donating Greg’s organs, most of which were in immaculate shape. Rodriguez told Mary Ann that Greg was the ideal candidate to be an organ donor, because he had passed away on a ventilator, which kept his organs active.

“The options we give them are: You can ‘pull the plug’ or, if you would consider leaving them on the ventilator, we can find people who need the organs,” says Silvestri. “We try to make sure they understand that this is a unique opportunity, because not very many people die on a ventilator at a hospital. Because the machine is pumping oxygen through the body, the organs are still functioning. You have to be on a ventilator to donate organs. Otherwise, they start to deteriorate right away.”

Silvestri says she understands why Greg’s family initially left the hospital without hearing about the possibility of organ donation; a lot of people do, she says.

“If it’s your child, imagine how much you’d want to sit there and hear us explain something like that,” she says. “The families listen to us, but they’re in that stage where they’re dealing with anger and denial and the beginning stages of grief. Mary Ann just wanted to get out of the hospital. It wasn’t like she was mad and not gonna wanna hear anything we have to say. That could not have been further from the truth.

“She was just dealing with her grief, and that’s how she was dealing with it at that moment.”

Contacted by phone, Mary Ann listened to Rodriguez intently. “Yes,” she understood the importance of organ donation. “Yes,” she realized it could help save a life, or several. “Yes,” her son would have wanted it that way.

And then, 30 more minutes into the conversation, she said something that stunned Rodriguez:

“My son,” Mary Ann said, “is on dialysis.”

In other words, her son David needed a kidney.

“I thought about David and him being on dialysis,” says Mary Ann, 48. “That’s how it started to move along.”

“But the strange thing is,” Gregory Kendrick says, “is that we never thought about that in the beginning. We were all so caught up in losing Greg, we didn’t think at the time that David could use his kidney. Mary Ann just told the lady on the phone that her other son was on dialysis, you know, just to tell her. We were just thinking they would go to someone who’s in desperate need of them. We had a son who was in desperate need himself, but we didn’t know how the process worked. We never thought of it.”

Just as his parents were initially unsure about donating Greg’s organs, so was David unsure about receiving a kidney from his brother. David had already turned Greg down before, years ago, when he was put on dialysis and Greg, unbeknownst to their parents, offered him one of his kidneys. David refused then, and he was refusing again now, even though his father described David’s situation as “dire straits.”

“He needed that kidney extremely badly,” Gregory Kendrick says. “Matter of fact, David was in the throes of giving up on getting better. He was threatening to not go back to his dialysis. But David had problems with his kidneys all his life. He’d seen numerous doctors through the years, but there wasn’t anything they could do.”

Despite his situation, the last thing David wanted to do was receive an organ from his brother; at that point, he wasn’t even able to accept his death.

“David wasn’t in agreement with it at all,” says Gregory Kendrick, 52. “I spent a lot of time trying to tell him that this was what Greg would have wanted. He offered it to him before, which we didn’t know about. That’s the type of person Greg was, caring and giving. David was just so upset. He kept saying, ‘I just want my brother back, I just want my brother back.’ We were finally able to convince him that this is what Greg would want and this is what the family wanted.

“But he’s still dealing with this.”

*

Gregory Kelly’s brother was not the only organ recipient. His lungs were donated to 60-year-old Jim Rapp of Rowlett. Rapp suffered from Alpha 1, or antitrypsin deficiency, a genetic disorder that can cause liver and lung disease. At its most vicious stages, the disorder requires a transplant.

Greg’s other kidney and his pancreas went to Lacette Green, 33, of Fort Worth. Diabetes had torn up her insides.

Greg’s heart saved a 67-year-old man in North Texas who is married and has two children. And his liver is now in the body of a 47-year-old North Texas man who is married; the names of these recipients have not been released, says Pam Silvestri, because they have not yet “reached out” to their donor family.

“They don’t have to. It’s not required,” Silvestri says. “We encourage them to at least write them a letter, thanking their donor family, but some donor families never hear from their recipients. Sometimes, the recipients have a strong sense of guilt — they’re alive after someone else has passed away. What we try to tell the recipient is, ‘For whatever reason, this person was going to die no matter what. It had nothing to do with you. It shouldn’t make you feel guilty.’ But sometimes they feel that way anyway.”

Receiving an organ transplant can be a difficult, expensive, frustrating — and rare — ordeal.

According to Silvestri, more than 83,000 people in the United States are awaiting lifesaving organ transplants. Texas has about 5,500 people on the list. And every day, 17 people die in the United States before the organs they need become available.

“I guess you start out optimistic,” says Rapp, who waited two years to receive donor lungs. “The longer you’re on the list, the more concerned you are about living long enough to receive one. You want to be sick enough to receive one but live long enough to receive one.”

Rapp is one of about 20,000 people a year lucky enough to have received a donated organ. More than 6,000 people become organ donors annually and with an average of three to four organs available from each donor, Silvestri says, more than 20,000 transplants happen each year.

“But many more people keep getting added to the list, so it’s growing exponentially,” she says. “When I started in 1995, the list was around 30,000. The reason the list is growing so quickly is because transplant works, and people want a second chance. So that’s a good problem to have, I guess.”

The heart, lungs, kidneys, pancreas and intestines can be donated, Silvestri says, and the liver, if it’s from a young, healthy donor.

But time ticks rather loudly.

“As soon as we start taking organs out of the donor, that’s when the clock starts ticking,” Silvestri says. “Once the organ is taken out, it’s carefully wrapped in several thick, plastic bags with preservation liquid. They’re stored in an ice chest, yes, just like on TV. With the heart and lungs, the transplant needs to be done within four to six hours. Other organs, it’s a little less delicate. With the liver, we have up to 18 hours. With the kidneys, about 48.”

It’s a seven-days-a-week, 24-hour operation, too. Rapp received his transplant phone call at 3 in the morning.

“I answered the phone and they said to him, ‘Jim, it’s time.’ He gave me a thumbs up,” says Rapp’s wife, Judy. “At that point, he was so excited, and still so sick, that he couldn’t breathe. He was on the back door, leaning on a chair, unable to move. It took him 20 minutes to get from the back door to the car. Once I got him in the car, he calmed down quite a bit. I think one reason why he couldn’t breathe was that, the whole time, we were very conscious of the fact that we only had a certain amount of time to get to the hospital.”

It’s just as exciting for those performing the procedure as those receiving it. “The nurses and EMTs and the medical professionals who are in on the transplant have very exciting jobs, flying around in Leer jets in the middle of the night,” Silvestri says. “Somebody is alive because of the job they do.”

*

The final step in organ donation is the possibility of a meeting between the donor’s family and recipients — and that’s where The Ballpark in Arlington gathering comes in. Lacette Green and Jim Rapp both wanted to “reach out” to the Kellys to thank them for giving them another shot at life, and The Ballpark seemed the perfect place to do it because the Rangers have organ-donor awareness games and related events.

Green, who had waited more than two years to receive a pancreas and kidney, was so insistent on meeting her donor’s family that she was going to take it upon herself to do so.

“I was going to initiate a meeting on my own when I found out they work in the same school district that I do,” says Green, a school counselor at West Handley Elementary School in Fort Worth. (Gregory and Mary Ann Kendrick both work for the Fort Worth school district). “They told me that I couldn’t, unless the family was interested. And then I found out the family was interested, and I could not have been happier. They gave me a chance to live.”

Although Green knew well in advance about the meeting at The Ballpark, Rapp did not. “We had just come back from a two-week vacation the night before,” he says. “And we were checking the e-mail and there was one saying the meeting was the very next day. I was delighted to meet Mary Ann, but I was overwhelmed with the media coverage and the short notice. I wish I would have had a moment to meet with her privately. I wish I had more words for her to describe how grateful I am.”

Like Green and Rapp, David Kelly, who is now off dialysis, is grateful, too. But he still battles with his brother’s death, and his own new lease on life.

“It’s still hard for me,” David says before he heads into the shadows of The Ballpark’s Gold Club. “Being his older brother, it’s hard. I miss him a whole lot. There’s a lot of struggle for me every day, but it’s getting better. I’m glad it was him [who donated the organ].

“He was a giving person.”

How to be an organ donor

Start talking. If you want to donate organs and/or tissue for transplants, signing a donor card or affixing a red “Donor” sticker to your driver’s license is important, but talking openly and often with family and friends will make it much more certain that your decision will be carried out. Your next-of-kin will be asked for permission before any lifesaving organs are harvested.

To download a donor card in Spanish or English, go to www.lifegift.org. For more information or to receive a donor card and sticker by mail, call LifeGift at (817) 870-0060 or the Southwest Transplant Alliance at (800) 788-8058. There is no age limit as long as your next-of-kin agrees at the time of donation.